History is a mainstay in the Islamic State’s propaganda. The group’s media units are constantly constructing and reconstructing historical narratives, compressing or stretching time and space when it suits their aims, and always seeking to inextricably merge the sacred and profane in the living history of its forever wars. It is hardly surprising that history is so important to the Islamic State. After all, the group builds its religious and jurisprudential credibility on the claim that it alone correctly and completely applies the Prophetic method (manhaj) for establishing an Islamic state. Consequently, history is also important for the perceived legitimacy and efficacy of its politico-military strategy. For the Islamic State, the ebbs and flows of history are products of the faithful’s fidelity to the divine.

If history flows as a series of timeless lessons for guiding the faithful, then the Islamic State’s propagandists see it as their role to draw out those lessons for their audiences. They do this by playing upon narratives of continuity, disruption, prophecy, and nostalgia in their propagandistic manipulation of history. Research into the psychology and neuroscience of memory may offer useful insights into how the Islamic State’s relentless approach to history wars in its propaganda can, over time, resonate with target audiences. For policymakers and practitioners, understanding both the different ways in which the Islamic State exploits history in its propaganda and the circumstances in which such messaging tends to resonate is vital.

Figure 1. Titlepage of From the Pages of History: From Jihad to Fasad, a recurring theme in Dabiq and Rumiyah.

The Propagandist’s Swiss Army Knife

History is the ultimate tool for the propagandist, providing a wellspring of narratives, heroes, villains, and events all ripe for revision and reinterpretation through a contemporary lens. During times of crisis, history is particularly alluring to the propagandist not only for inspirational stories of past glories that become blueprints for remaking the present but also due to the susceptibility of audiences to such narratives. Violent extremists are almost always driven by a belief that it is their responsibility to correct the arc of history in accordance with some historical ideal. With this often comes an acute sense that they are the contemporary heirs of a living history that inextricably connects them to the past and future. To appreciate the potential potency of history as a propaganda tool it is useful to consider how it may exploit memory processes.

A growing body of research suggests that the act of retrieving a memory is, in many ways, a process of reconstructing that memory whereby, over time, one is essentially remembering the previous memory rather than the actual event itself. These processes of memory retrieval can lead to several types of memory distortions: imagination inflation (where imagined experiences and events are infused into the memory by varying degrees), gist-based memory errors (where specifics are lost and generalities take over the memory), and post-event misinformation (in which false information is infused into the memory). It is not that memory processes are inherently flawed, but rather that such distortions are the by-product of important adaptive processes that are crucial to the overall efficiency of memory functions. Post-event misinformation and imagination inflation may be particularly relevant when considering how and why propagandistic historical narratives can resonate with audiences, and how and why the resiliency of such narratives impact target audience perceptions if left unchallenged.

History in Daesh’s Forever War

The main function of the Islamic State’s exploitation of history is to weave itself into the fabric of Islam’s history by framing the Islamic State as the contemporary heir of a single, protracted struggle that stretches back to the Prophet Muhammed and indefinitely forward to End Times. In the hands of the Islamic State’s propagandists, history becomes a multifaceted propaganda tool characterized by four types of narratives that variously shape the perceptions and polarize the support of target audiences. The Islamic State’s interplay of continuity, disruption, prophecy, and nostalgia narratives is designed to create self-reinforcing cycles that contribute to the overarching logic of its propaganda activities.

Of the four narrative types, continuity narratives are the most common in the Islamic State’s propaganda. These messages construct historical arcs that reinforce the dichotomous lineages and legacies of Islam’s heroes and past glories with the ancient animosities and malevolence of its enemies. These are narratives that don’t just provide historical context for the present, but also seamlessly connect the past, present, and future. When the Islamic State’s top leaders have delivered milestone speeches in the group’s evolution, continuity narratives have featured heavily. For example, Abu Bakr al-Baghdadi’s 2013 announcement formalizing his group’s expansion from Iraq to Syria included a detailed retelling of the Islamic State’s various name changes as signposts of its ascension in applying the Prophet method.

Another important aim of continuity narratives is to identify historical precedents to explain the present. Having lost all its territorial control and reverted to a global insurgency, the Islamic State’s propaganda is now filled with historical narratives emphasizing that this is all part of a never-ending struggle in which patience is not only a virtue but also a strategic necessity. For example, a recurring theme in recent An-Naba editorials has been to reference a famous historical battle – whether the struggles of the Rightly Guided Caliphs centuries ago (issue 375) or the 2004 Battle of Fallujah (issue 370) – and to declare that its current battles are part of the same protracted war. This all contributes to embedding the group into Islam’s history as evidenced in An-Naba’s Ramadan editorial (issue 383):

Ramadan was a month of brilliant pivotal events in the far distant and close history of the Ummah of Islam, starting with the Battle of Badr, the first decisive battle in the history of Muslims, then the conquest of Mecca… and last but not least, the declaration of the return of the Caliphate on the prophetic method. Indeed, the men of Islam through the ages transformed the texts of the two holy revelations into actions through which they achieved glory for their Ummah, the effects of which are still being witnessed as of today.

In contrast to continuity narratives, disruption narratives focus on figures and events that ruptured history’s trajectory for better or worse. Inevitably, disruption narratives tend to feature prominently in the Islamic State’s propaganda during periods of strategic transition. For instance, the Islamic State’s propaganda campaign surrounding the announcement of its caliphate through June and July of 2014 presented the group as destroying the borders of the Sykes-Picot agreement as jahili relics of a shameful modern history. Almost ten years later, and with its territorial caliphate decimated, the Islamic State’s propagandists flipped the narrative to blame a lack of support for its collapse and the ummah’s subsequent tribulations. For example, in the aftermath of the 2023 Kahramanmaras earthquake, an An-Naba editorial (issue 381) titled “The People of Sham and the Betrayal of the World” lamented that “if the Muslims fulfilled the obligation and duty of jihad… as it should be, then there would have been no borders that fragmented their unity and their countries.”

Prophecy narratives focus on the message of historical figures that have predicted the future. The Islamic State regularly draws on the Quran and Hadiths to highlight how Islam’s greatest heroes had predicted how circumstances would play out – typically to reinforce overarching continuity and disruption messaging. While less common, prophecy narratives are designed to be high-impact messages due to their explicit merging of the sacred and profane. The Islamic State’s most religious and emotionally charged examples of prophecy narratives address End Times. Apocalypse prophecies have played a persistent role in the Islamic State movement’s propaganda since its formative years under Abu Musab al-Zarqawi and through its caliphal period. It remains important now, too, as a global insurgency. For instance, An-Naba’s editorial for issue 374 highlights the Prophet’s declaration that as End Times near many in the ummah will abandon their faith as a reminder to the audience to remain committed as challenges increase.

Finally, nostalgia narratives offer idealized presentations of the past as a source of inspiration for the present. Two types of nostalgia narratives have been featured in the Islamic State’s propaganda since its territorial collapse. Caliphal nostalgia narratives venerate and pine for the glory days and unfulfilled potential of the group’s short-lived caliphate while manhaj nostalgia glorifies the credibility and efficacy of its method for establishing an Islamic State. Caliphal and manhaj narratives are designed to be self-reinforcing. It follows that the glories of the past that saw the establishment of the caliphate were achieved by purely applying the prophetic method. In turn, the determined and uncompromising application of its manhaj guarantees the achievement of the caliphate. This is best summarised in the conclusion of An-Naba’s editorial for issue 383: “The condition of the Ummah in this time will not be corrected except by what the condition of the Ummah in the past was corrected. Therefore, it is necessary to proceed on what they proceeded and adhere to what they adhered.”

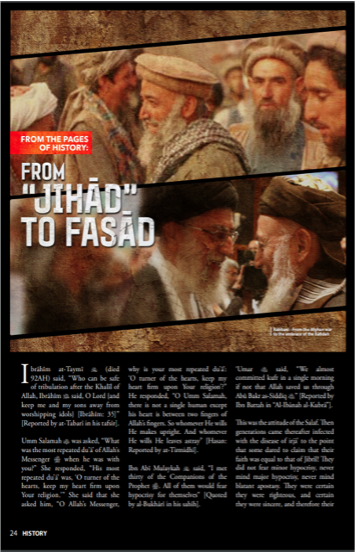

Figure 2. The city of Mosul in November 2015 (left) and July 2017 (right). Images from DigitalGlobe appearing in a New York Times article.

Winning the History Ground War

It can often be difficult for policymakers and practitioners to understand how the Islamic State movement manages to re-emerge in locations where the group had once wreaked havoc. From Mosul to Marawi, there are a range of reasons why the group can respawn, including extant operational awareness, the persistence of local support networks, and the impact of its relentless local influence efforts. The latter almost always includes messaging that exploits history. Policymakers and practitioners need to appreciate that the Islamic State’s history propaganda is more likely to resonate when (a.) its propaganda is left unchallenged in the information theatre, (b.) the group shares a common history and identity with the population, and (c.) life in those communities has not discernibly improved.

To win the history ground war, the Islamic State’s propaganda must be relentlessly challenged in a manner that is strategic and led by local actors. Priority should typically be given to proactive and pre-emptive messaging that exposes the Islamic State’s exploitation of history as a sign of being out of touch, marketing a past that never existed, and revealing a deluded sense of reality. This type of messaging also helps to “prime” audiences for how they respond when exposed to the Islamic State’s propaganda. A vital step towards empowering local actors and building resilience in local communities is the methodical preservation of history and ensuring that it is memorialized and publicly accessible for future generations. Ultimately, propagandistic historical narratives are merely blunted with even the best-designed and deployed strategic communications. Defeating such narratives is only possible by improving the lives of vulnerable communities to render pining for the past obsolete.