THE SOUTHERNMOST ISLANDS in the Philippines’ archipelago have been ravaged by decades of wars that rarely attract global media attention. Then, for a fleeting moment in 2017, the world watched as Islamic State militants laid siege to Marawi City for five months, inflicting untold damage on Marawi’s streets and people.

The perpetrators of the Marawi siege intended to derail ongoing peace efforts, but their attack had the opposite effect. Within two years, the Bangsamoro Autonomous Region of Muslim Mindanao (BARMM)—an autonomous region with a population of about 5 million people—would be established, heralding the most promising opportunity for sustainable peace in over a generation. Today, the success of those peace efforts rests heavily on whether a variety of defector programs can sufficiently hollow the ranks of armed groups and transition former combatants back into their communities.

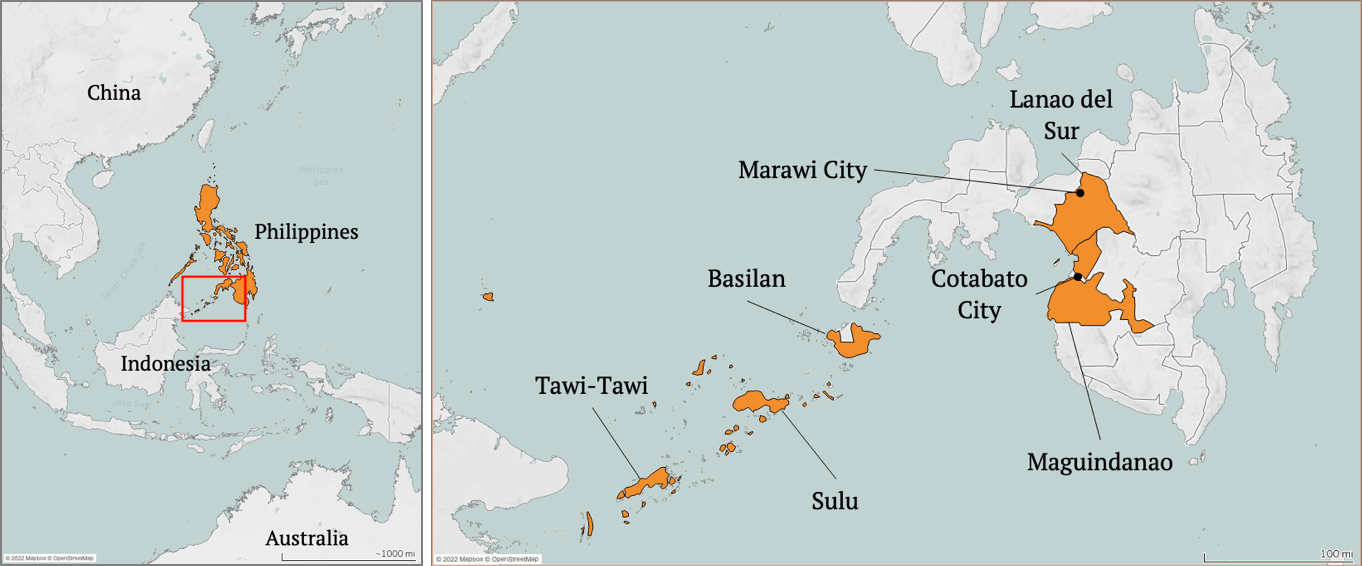

The Bangsamoro Autonomous Region of Muslim Mindanao (BARMM)

For all the complex political and bureaucratic dynamics involved in the formal peace process, it will be a handful of national, regional, and local government officials, military personnel, civil society leaders, and former guerrillas on the frontlines of the Bangsamoro’s defection and reintegration challenge that may tip the balance of a fragile peace. In a recent article for The New Humanitarian, I reported on the daily struggles of defector programs from the floodplains of Maguindanao to the jungles of Lanao del Sur. Here are three lessons for practitioners that emerged from those field interviews.

1. Fear and the politics of dashed expectations are powerful drivers “in” and “out” of armed groups.

Across dozens of interviews conducted throughout the BARMM this year, perhaps the most cited motivation for joining or staying in a violent group was fear. Fear of an uncertain future, of being isolated, of not being able to provide for one’s family, of a life and death without dignity. The normalization track of the peace process seeks to decommission 40,000 ex-combatants of the Moro Islamic Liberation Front (MILF). So far, less than half of this figure have been processed, and the reluctance of many ex-combatants to handover their arms is out of fear of other armed groups.

As such, the success of the normalization track is intimately tied to the success of a hodgepodge of other defector and reintegration programs targeting violent extremists like local ISIS affiliates, various factions of the Bangsamoro Islamic Freedom Fighters (BIFF), and the Abu Sayyaf Group. Fear can also provide powerful motivation out of a life of violence. As an ISIS defector coordinator working in Maguindanao explained to me, “Convincing surrenderees to leave violent groups is like convincing the people to support peace. Everybody is scared. Both sides offer different opportunities for how to deal with that fear. The people must choose.”

The politics of dashed expectations is another powerful lever. Bangsamoro officials, Philippine Army officers, and civil society leaders regularly highlighted how the disparity between expectations and reality had, to varying degrees, motivated most defectors from armed groups irrespective of their ideological motivation. But the politics of dashed expectations tends to be a more powerful tool in the hands of peace spoilers who use it transform fear into loathing for the status quo. For those seeking to advance peace efforts, managing the expectations of defectors and local communities is critical to buy valuable time for implementation. Ultimately, delivering on promises is the only way to effectively counter spoilers exploiting fears and the politics of dashed expectations to lock people into cycles of violence.

2. Leverage “carrots” and “sticks” to attract defectors and facilitate reintegration.

Mapping pathways “in” and “out” of armed groups is a vital exercise for not only informing reintegration design and implementation, but also ensuring that practitioners remain deeply engaged with defectors, local communities, and, wherever possible, members of armed groups. Understanding the psychosocial and strategic factors that “push” and “pull” people in and out of armed groups can also help to inform more creative approaches to defection and reintegration opportunities. A combination of “carrots” and “sticks” are important for increasing the likelihood both that members of armed groups will defect, and that local communities will accept them. For instance, in the Bangsamoro, amnesty windows have been used to provide members of armed groups with a defined period to defect and participate in reintegration programs. By clearly communicating to members of armed groups the opportunities to defect and reintegrate (“carrot”), the narrow window being offered for participation (limitation), and the potential consequences of non-participation (“stick”), this combination of carrots and sticks can be a powerful driver.

It is also important to match different levers with specific defection and reintegration goals and contexts. For instance, to encourage participation in the formal normalization track of the peace process, it is vital to lower obstacles and maximize incentives to participate. However, programs targeting violent extremists (and other armed groups outside formal peace efforts) may look to increase the “cost of redemption” for those defecting and reintegrating to increase the perceived value of participation and demonstrate to local communities that former violent extremists are not benefiting from their violent past. IDPs in Marawi have previously expressed anger and frustration that “ISIS defectors get more benefits than IDPs,” a trend that has also emerged in other contexts involving Islamic State militants in Iraq and Syria, Afghanistan, and elsewhere. Managing these “costs of redemption” is a delicate balancing act, one that should be selectively applied on a case-by-case basis by methodically drawing on the best available evidence.

3. Defection and reintegration challenges are fundamentally a competition of persuasion.

Almost everyone I interviewed saw their role in motivating defections and reintegration back into the communities as a persuasion contest. At its core, this is a competition between peaceful and violent solutions to address problems in the Bangsamoro. The region’s fate largely rests on who will be more persuasive. Kinship ties often play a vital role for getting people involved in armed groups, and those same networks can be crucial to getting people out of a life of violence. In conflict areas of Maguindanao, kinship ties with local violent extremist groups like the Bangsamoro Islamic Freedom Fighters (BIFF) have often made local communities reluctant to expose the rebels. To effectively navigate these barriers, local defector coordinators must build relationships of trust with local communities. As that ISIS defector coordinator in Maguindanao explained to me, “It is then that the communities, their family and friends, encourage their loved ones to return to a peaceful life… We just make sure we’re there when they are ready.” Kinship networks are powerful messengers that are oftentimes much more likely to directly persuade family and friends to leave armed groups than government officials, the military, or representatives from international NGOs.

When the defection and reintegration challenge is understood as a competition to persuade, the essential role of strategic communications becomes clear. Engaging in public messaging does not need to be complex, nor should it be ad hoc. By mapping the pathways in and out of violent armed groups, harnessing multisector relationships, and adopting a methodical, evidence based, and persuasive approach to messaging, defector and reintegration programs can significantly amplify the reach and impact of their efforts.

A Peace Won House-to-House with Regional Security Implications

There are more reasons to be hopeful than pessimistic about the Bangsamoro’s future. In its first three years, the Bangsamoro Transition Authority (BTA)—which was created alongside the BARMM in 2019 to help oversee the transition—made solid progress on the two-track peace process, especially given the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic. As it now enters the final three years of its transition extension, there is no room for failure. The stakes are incredibly high for not only the Moro people, but the nation and broader region. In the aftermath of previous peace process failures, bloody conflict inevitably ensued fueled by disgruntled breakaway factions from existing armed groups. Now, Islamic State aligned groups operate almost exclusively in the BARMM’s territories and are poised to exploit opportunities to plunge the islands’ war-weary inhabitants into chaos once again.

With Europe hampered by the war in Ukraine, Islamic State affiliates surging in Africa, multiple humanitarian crises afflicting Taliban-ruled Afghanistan, and global economic recession threatening stability in many theaters, it is easy to forget the little islands of Mindanao. This would be a mistake because there are crucial regional implications at play here, too. For decades, the Armed Forces of the Philippines (AFP) have been dealing with internal security threats. The promise of peace in the nation’s restive south raises hopes that the AFP could then shift its posture to deal with regional (external) threats. Put simply, supporting a stable and prosperous BARMM is not only in the interests of the Philippines, but also the United States and other Western allies. There is much work still to be done, and the international community—especially the United States, which has been largely absent from supporting Bangsamoro peace efforts—must be more engaged.