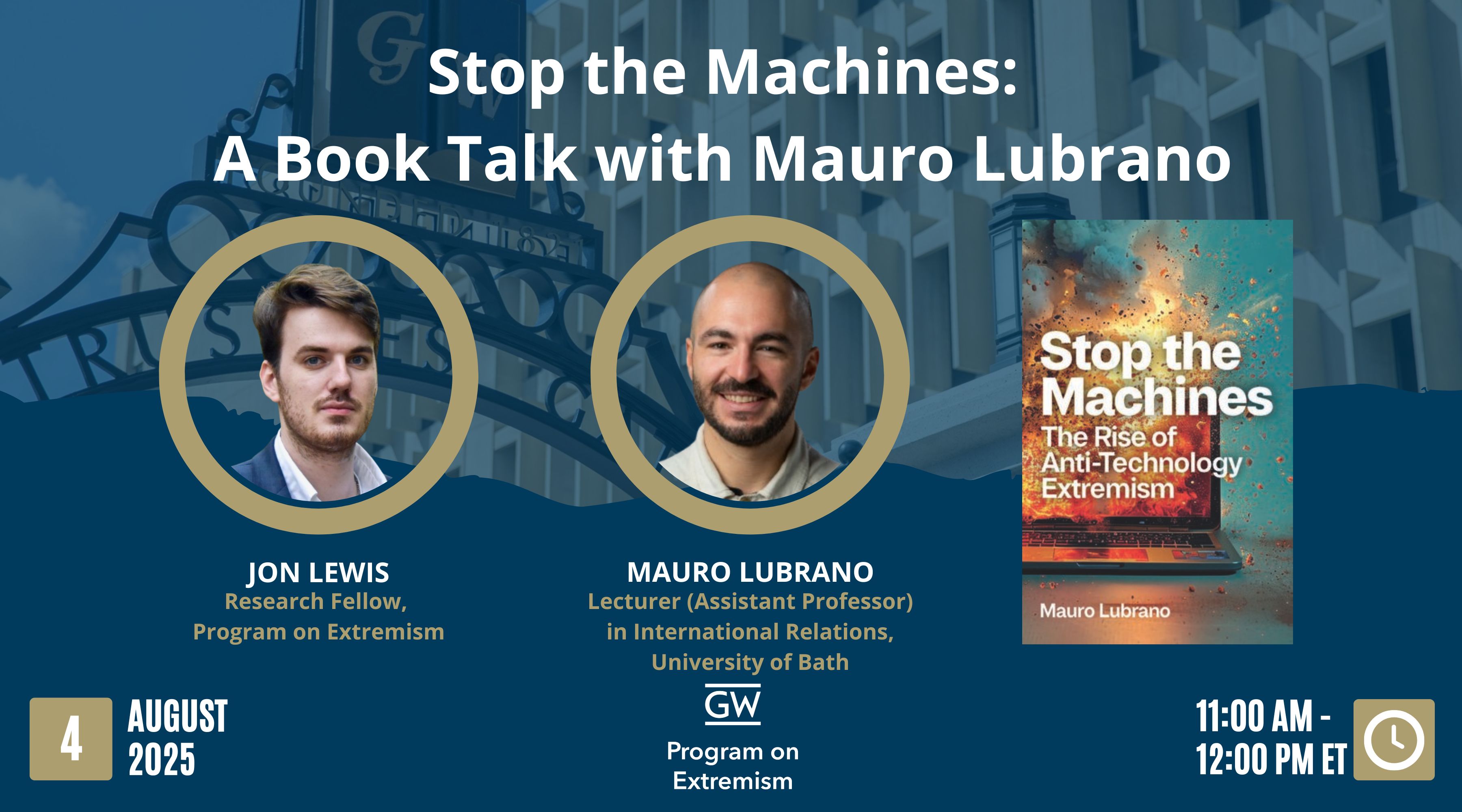

Stop the Machines: A Book Talk with Mauro Lubrano

On August 4, 2025, the Program on Extremism held a timely discussion with Dr. Mauro Lubrano, Lecturer (Assistant Professor) in International Relations in the Department of Politics, Languages, and International Studies at the University of Bath, to explore his new book, Stop the Machines: The Rise of Anti-Technology Extremism. In an extremist ecosystem increasingly driven by grievances and narratives, the intellectual flexibility of this anti-technology ideology represents a potent emerging threat. The conversation, moderated by Research Fellow Jon Lewis, examined the origins and evolution of anti-technology extremist violence across the globe, from insurrectionary anarchists to eco-extremists and eco-fascists.

On August 4, 2025, the Program on Extremism (PoE) at The George Washington University hosted a virtual book talk with Dr. Mauro Lubrano to discuss his new book, Stop the Machines: The Rise of Anti-Technology Extremism. Research Fellow Jon Lewis moderated this event.

The conversation examined anti-technology extremism. Dr. Lubrano argues that this form of extremism emerged as a reaction to the Anthropocene as an attempt to reverse the age of human dominance. This vast movement varies from a class struggle against “techno-elites” to the defense of things like white supremacy or even nature.

Dr. Mauro Lubrano began this discussion by reflecting on how he came to study this topic. In 2019, Dr. Lubrano was a PhD candidate at the University of St. Andrews, specializing in political violence and terrorism. Ironically, he was focused on how groups use technology, rather than how they do not. He wanted to understand if anti-technology extremism could become a driver of political violence.

Lewis opened the discussion by asking about the history of anti-technology sentiment. Dr. Lubrano explained that in order to understand how anti-technology ideas emerged, evolved, and manifest themselves nowadays, one needs to understand where they came from and how they have evolved across history. Anti-technology grievances can be traced back to the Industrial Revolution, when automated processes replaced human labor. Whereas this sentiment focused on material security, the evolution of anti-technology sentiments and extremism takes a more ontological narrative: that technology will redefine what it is to be human, and what it is to live among each other and nature.

In his book, Dr. Lubrano identifies three main ideologies in the “war against machines:” insurrectionary anarchists, eco-extremists, and eco-fascists. Insurrectionary anarchists, paradoxically, have historically embraced technology more than the others. Eco-extremists emerged in Mexico in the early 2010s, and found their origins in anti-colonial history in South America. Eco-fascists trace their roots to German Romanticism. Despite their differences, these groups view the notion of technology as a means of surveillance, dominion, and a means of control to enslave humanity. Technology, according to them, cannot be reformed or changed, so it must be dismantled.

Many groups draw influence and critique from Theodore Kaczynski’s work. They attack technological “edifices of power,” such as infrastructure, research centers, laboratories, and sometimes the people who represent them. For example, insurrectionary anarchists from the Informal Anarchist Federation kneecapped a CEO of a nuclear engineering firm and sent parcel bombs to Swiss nuclear executives. While these groups rarely employ lethal violence, it is the “exception rather than the rule.”

Concluding the discussion, Dr. Lubrano returned to his driving question: Can anti-technology extremism become a driver of political violence? His answer? It already has. He warned that as technology advances, anti-technology sentiment will too. If left unchecked and unaddressed, he warns the ideologies will become increasingly dangerous.