PDF Version

ON JULY 31, 2022, the U.S. killed Ayman al-Zawahiri, the emir of al-Qaeda, in a drone strike in Kabul, Afghanistan. Zawahiri had served as al-Qaeda’s global leader since his longtime comrade, Osama bin Laden, was killed by Navy SEALs in May 2011. Zawahiri was not merely a figurehead at the time of his demise. According to a senior administration official, the elderly Egyptian “continued to provide strategic direction to al-Qaeda’s affiliates worldwide, calling for attacks on the United States.”

Indeed, Zawahiri’s death was a big deal not only for the U.S., but also jihadists around the globe. His tenure at the top of al-Qaeda was hardly smooth. The rise of the Islamic State wreaked havoc on his organization. But Zawahiri’s network proved to be resilient. As members of al-Qaeda’s branches (or “affiliates”), thousands of jihadists from Africa, through the heart of the Middle East and into South Asia owed their fealty to Zawahiri. Which makes al-Qaeda’s silence concerning Zawahiri’s death surprising.

More than seven months have passed since Zawahiri was killed. Typically, a leader of Zawahiri’s standing receives glowing eulogies from his fellow jihadists. But al-Qaeda’s surviving senior leaders have not uttered one word of praise for their fallen emir. Nor have they publicly named his successor. Al-Qaeda’s regional branches have been mum as well.

A newly released report from a U.N. Security Council monitoring team offers two reasons for al-Qaeda’s silence.

First, Zawahiri’s presence in Kabul was “an embarrassment for the Taliban,” which seeks “legitimacy as a governing authority” and has long denied that Afghanistan is home to senior al-Qaeda figures. The Taliban’s denials are not credible, but it persists in lying and al-Qaeda does not want to create more problems its longtime allies.

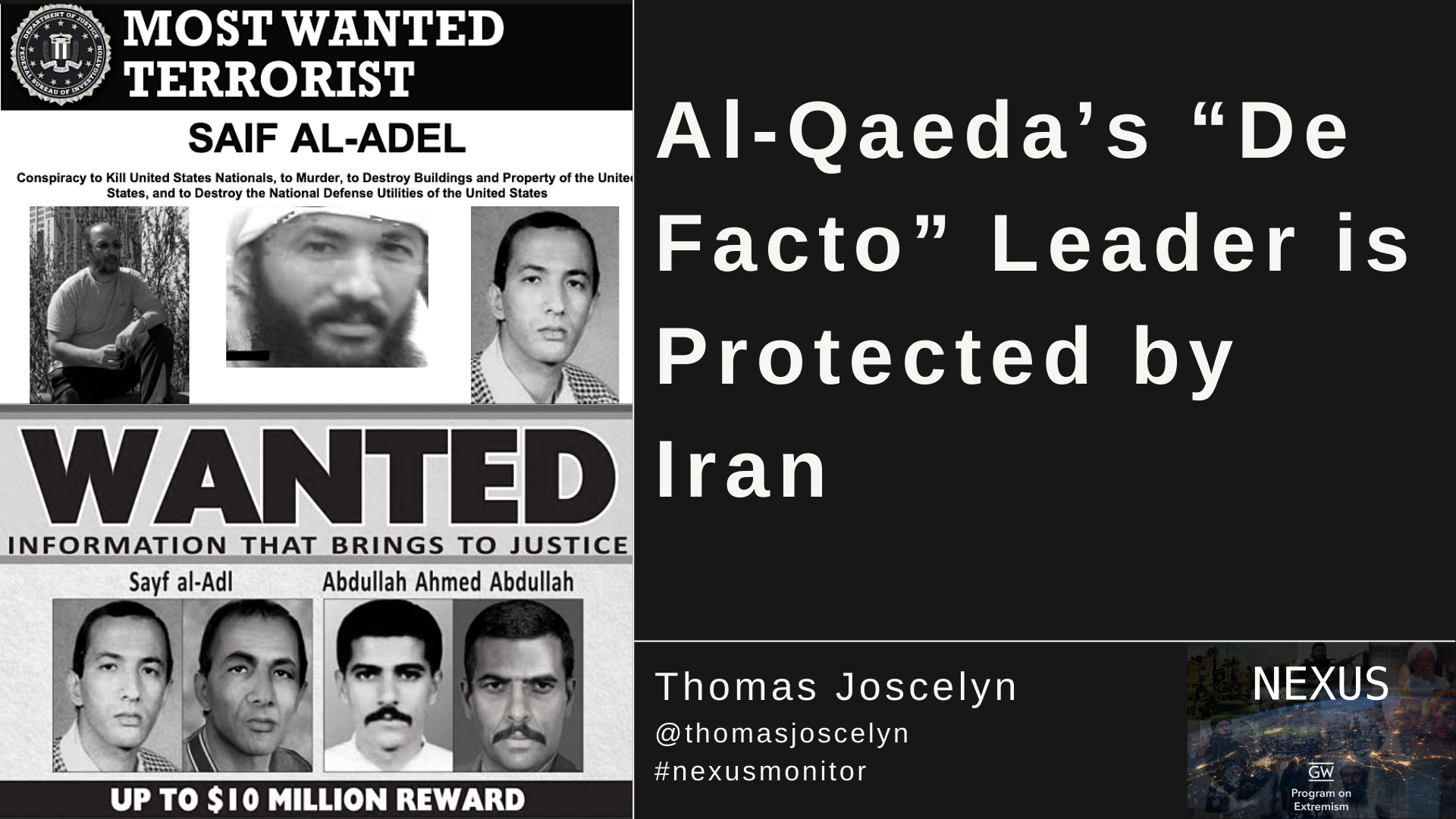

Second, “many Member States” have concluded that one of Zawahiri’s closest colleagues, Sayf al-‘Adl, is “already operating as the de facto and uncontested leader of the group.” Why hasn’t al-Qaeda announced al-‘Adl’s succession? UN Member States point to al-‘Adl’s “continued presence” inside Iran, which raises “difficult theological and operational questions” for al-Qaeda. Simply put, the Sunni jihadists of al-Qaeda don’t want to admit that they rely on the Shiites of Iran for safe haven. And the Iranian regime does not want to admit it harbors some of al-Qaeda’s leaders.

As Sayf al-‘Adl’s biography shows, however, this is nothing new. The Iranians have long harbored him and other al-Qaeda figures.

Al-Qaeda began working with Iran and Hezbollah in the early 1990s

Sayf al-‘Adl, a former lieutenant colonel in Egypt’s special forces, joined the Egyptian Islamic Jihad (EIJ) in the late 1980s. The EIJ was a terrorist group that targeted the Egyptian government throughout the 1980s and eventually merged with Osama bin Laden’s operation prior to 9/11. Though the formal merger between the two was not consummated until either 1998 or the summer of 2001, depending on which sources one consults, the EIJ’s men were central to al-Qaeda’s operations by the early 1990s. For instance, according to the State Department, al-‘Adl provided training for other al-Qaeda operatives “as early as 1990.” And in 1992 and 1993, “he provided military training to AQ operatives and Somali tribesmen” who fought against U.S. forces during the infamous “Black Hawk Down” battle in Mogadishu, Somalia.

Al-Adel’s relationship with the Iranian regime and its chief terrorist proxy, Hezbollah, also dates to the early 1990s. From 1991 to 1996, Osama bin Laden was based in Sudan and its Islamist regime maintained friendly relations with the Iranians. According to the 9/11 Commission’s final report, Osama bin Laden reached out to Iran and its master terrorist, Imad Mughniyah, for assistance. Bin Laden wanted Iran and Hezbollah to show his men how to conduct simultaneous suicide attacks, such as the 1983 Beirut bombings, which targeted the U.S. Marine Barracks and the headquarters for French paratroopers. Those bombings, which left 241 U.S. Marines dead, and other terrorist operations eventually led the U.S. to withdraw from Lebanon. And bin Laden surmised that similar attacks against U.S. interests elsewhere could force America to retreat from the world stage once again. Mughniyah was the mastermind of those bombings and other attacks against Western interests in Lebanon throughout the 1980s. He agreed to train bin Laden’s men -- including Sayf al-‘Adl.

The 9/11 Commission later concluded that this training gave al-Qaeda the “tactical expertise” necessary to carry out the 1998 U.S. Embassy bombings in Kenya and Tanzania. The bombings, which killed 224 civilians and wounded thousands of others, were al-Qaeda’s deadliest attacks prior to the 9/11 hijackings. Sayf al-‘Adl has been wanted for his role in the bombings ever since.

During the U.S. Embassy bombings trial, which took place in the early 2000s, two former al-Qaeda men later told a New York court about the training. Ali Mohamed, another EIJ veteran who worked for al-Qaeda, told the court that he set up the security for the meeting between bin Laden and Mughniyah. As a result of that meeting, Hezbollah agreed to help by providing explosives and training on how to use them. An al-Qaeda defector named Jamal al-Fadl also told the court that al-‘Adl was part of the cadre that received Iran’s and Hezbollah’s explosives training in Lebanon and Iran. After the U.S. Embassy bombings, al-‘Adl relocated to southeastern Iran, where he “lived under the protection of Iran’s Islamic Revolutionary Guard Corps.”

The explosives training provided by Hezbollah and the Iranians was not the end of the Iran-al-Qaeda nexus. It was just the beginning.

Throughout the 1990s, U.S. officials tracked al-Qaeda operatives who were operating inside Iran. For instance, former counterterrorism official Richard Clarke writes in Against All Enemies that “Iran provided al Qaeda safe haven before and after September 11,” with al Qaeda “regularly” using “Iranian territory for transit and sanctuary prior to” the hijackings. Clarke added that “Al Qaeda’s Egyptian branch, Egyptian Islamic Jihad, operated openly in Tehran,” so it “is no coincidence that many of the al Qaeda management team, or Shura Council, moved across the border into Iran after U.S. forces invaded Afghanistan.”

Al-‘Adl was part of al-Qaeda’s management team inside Iran.

Post-9/11 reporting on al-Adel’s activities inside Iran

U.S. intelligence continued to track Sayf al-‘Adl inside Iran in the months and years following 9/11, though his status was not always clear.

George Tenet, the former Director of Central Intelligence, discusses some of this intelligence in his autobiography, At the Center of the Storm. The CIA learned that from the end of 2002 through the spring of 2003, al-Qaeda was attempting to purchase Russian nuclear devices. While living inside Iran, al-‘Adl was involved in these discussions. However, he warned others within al-Qaeda’s hierarchy that the prospective deal could be a scam. Tenet writes that the Iranian regime was holding al-‘Adl and other senior al-Qaeda figures “under a loose form of house arrest” at the time. However, given that they were trying to acquire the world’s most dangerous weapons, the Iranians’ version of “house arrest” obviously did not prevent al-Qaeda’s men from going about their terrorist business. According to Tenet, the CIA informed the Iranian regime that the U.S. knew about their conspicuous houseguests. The CIA “hope[d]” the Iranians “would recognize our common interest in preventing any attack against U.S. interests.”

It is not clear when, exactly, the CIA reached out to the Iranian regime. However, there were ample reasons for alarm. The U.S. reportedly obtained intercepts and other intelligence indicating that al-Qaeda’s Iran-based leadership had a hand in the May 12, 2003, Riyadh apartment bombings, which killed more than 30 people, as well as the May 16, 2003, bombings in Casablanca, Morocco, which left 45 people dead.

There is little publicly available reporting about al-‘Adl’s activities in the years that followed. It is possible that the Iranians’ “house arrest” of al-Qaeda’s men became more stringent after the Riyadh and Casablanca bombings. It is also possible that al-Qaeda’s leaders simply adapted and were more careful about how they communicated with the outside world. The truth may be somewhere in between. We do know that al-Qaeda eventually objected to the arrangement, demanding that the Iranians let al-‘Adl and others go free.

In 2015, the Iranians freed al-‘Adl and four other senior terrorists as part of a hostage exchange. According to press reporting at the time, the five al-Qaeda veterans were traded for an Iranian diplomat who had been kidnapped in Yemen. Online al-Qaeda insiders confirmed that the exchange took place. Three of the five made their way to Syria, where each was killed. However, al-‘Adl and one of his longtime compatriots, another Egyptian al-Qaeda leader known as Abdullah Ahmed Abdullah (a.k.a. Abu Muhammad al-Masri), remained inside Iran.

Increased scrutiny of al-‘Adl’s activities inside Iran

From 2015 onward there has been an uptick in reporting about al-Adel’s portfolio within al-Qaeda’s global network.

In July 2018, the UN Security Council’s Islamic State and al-Qaeda monitoring team reported that al-‘Adl and al-Masri were playing a more “prominent” role than they had in the past. Member States informed the UN that the two were working to undermine the power of Abu Muhammad al-Julani, who leads a group known as Hay’at Tahrir al-Sham (HTS). HTS, which was once known as Jabhat al-Nusrah, an official branch of al-Qaeda, disassociated itself from the international terror network in 2016. That move proved to be controversial within jihadi circles over time and the Iran-based al-Qaeda leaders worked with breakaway factions to subvert al-Julani’s standing. One of the group’s they worked with is Hurras al-Din (HAD), which is led by other al-Qaeda veterans.

Interestingly, the latest UN Security Council report indicates that, according to one Member State, HAD continues to receive “direct instructions from Sayf al-‘Adl.”

In Aug. 2018, the State Department raised the reward for information on the whereabouts of al-‘Adl and al-Masri from $5 million to $10 million. Both were wanted for their role in the U.S. Embassy bombings, among other terrorist acts.

Then, on Aug. 7, 2020, Israeli operatives assassinated Abu Muhammad al-Masri and his daughter in the suburban Pasdaran district of Tehran. The assassination, which was reportedly conducted at the request of the U.S. government, occurred on the anniversary of the U.S. Embassy Bombings. Neither the Iranian regime, nor al-Qaeda has publicly admitted that al-Masri was gunned down. But from that time until now, Sayf al-‘Adl has surely known that the U.S. and its allies could try to bring him to justice in a similar manner.

As this summary shows, it is entirely unsurprising that Sayf al-‘Adl is thought to be al-Qaeda’s new “de facto” leader. Nor is it surprising that he is still inside Iran. He’s been working with the Iranians, on and off, for three decades.