PDF Version

FROM IRAQ AND SYRIA to the Philippines, defection and reintegration strategies are central to government and civil society efforts to counter and prevent an Islamic State resurgence. Nowhere else are such activities seen as more urgent than camps and detention facilities across Iraq and northern Syria filled with people who not only once lived under the Islamic State’s control, but many of whom still, to varying degrees, may remain committed to the group. The immense challenges associated with these efforts are made even more complicated by the fact that the Islamic State has its own defection and reintegration strategies that not only directly compete with government and civil society programs, but often predate them by over a decade.

The Islamic State’s defection and reintegration strategies played a key role in its historical successes and are now a crucial tool both in its revival efforts in the Levant and as an export to affiliates. It will be essential for defection and reintegration practitioners to understand the Islamic State’s approach in order to outcompete the group. In areas where the Islamic State is actively operating, understanding the movement’s defection and reintegration strategies should be a prerequisite for practitioners working in this space.

The Cost of Redemption

Throughout its history, the Islamic State has practically applied its multiphase insurgency campaign to enable its creed of forever war. While control of territory and cities are anomalies in its history of booms and busts, those locations where it has had its greatest successes have become strategic anchor points to which the group often returns. The group's tendency to return to places known during times of hardship is not only a human trait but also part of a propaganda strategy that plays upon memory and nostalgia to reconstruct history.

There is another reason for this trend: the Islamic State deploys its own defection and reintegration strategies to give populations the opportunity to defect from the ranks of its enemies and (re)integrate into the Islamic State. The group deploys defection and reintegration strategies to simultaneously grow its capabilities while eroding those of its adversaries. During its guerrilla campaign phases it especially targets former combatants from the army and police to boost its military, law enforcement, and intelligence capabilities. The group also seeks to attract government bureaucrats, businesspeople, and skilled workers to enhance its overall capabilities while degrading its enemies. The closer the group moves towards the tamkin (consolidation) threshold when it begins to consider conventionalizing its operations, its defection and reintegration strategies increasingly incorporate whole communities, targeting influential tribes and strategic villages and often culminating in public pledge events.

The Islamic States' approach to defection and reintegration is surprisingly adaptable and sophisticatedly designed to directly outcompete equivalent government and civil society programs. For instance, the Islamic State’s defection and reintegration strategies are applied across the full spectrum of its insurgency phases from when it is running guerrilla politico-military operations through the tamkin threshold and when it has established its state apparatus. This flexibility is also evident in the group’s application of its defection and reintegration strategies in both regions of previous control and areas it aspires to control.

Fighters from the Islamic State's Kirkuk province re-pledge their allegiance to the new caliph, Abu al-Hasan al-Hashimi al-Qurashi, following his predecessor's death in February 2022. Photo: Wilayat al-Iraq - Kirkuk propaganda release, March 2022.

The Islamic State adapts its activities to synchronize with its campaign phases – whether mounting a grinding guerrilla war or on the verge of controlling a town or city. The general trend is that when the group is comparatively weak, it prioritizes those ‘decisive minorities’ that have a disproportionate impact on who and how the largely apolitical majority in a community will likely support. The Islamic State would covertly approach tribal leaders, politicians, military, police, and even business leaders to shift their allegiances to the Islamic State and contribute to its agenda.

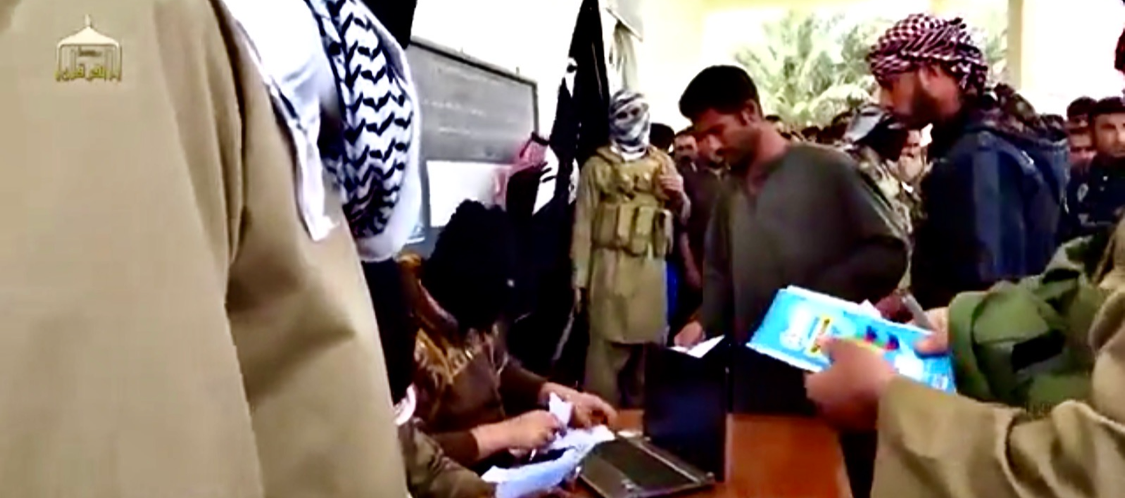

Deploying a mix of “carrots” and “sticks,” the Islamic State engages in a variety of activities that peace and P/CVE practitioners would immediately recognize. This includes strategies such as reconciliation engagements, conflict resolution activities, the use of amnesty windows, offering socioeconomic packages, vocational training, and security protections. The threat of lethal force is, of course, never too far away. Propaganda is also central to these efforts not just to attract defectors and incorporate them into the Islamic State, but to render it near impossible for them to rescind (even months or years later) by featuring newly reintegrated defectors in public messaging.

From Guerrilla Struggle to Caliphate and Back

The integration of defectors into the Islamic State’s ranks has been a feature of its efforts to build momentum behind its guerrilla struggle, formalize popular support when it is conventionally strong, and rebuild its ranks. Under Zarqawi’s leadership almost two decades ago, his insurgency looked to deeply embed its roots into Iraqi society by opportunistically exploiting vulnerabilities to attract defectors from the government and military professionals. Historical predecessors to the Islamic State—Al-Qaeda in Iraq (AQI) and the Islamic State in Iraq (ISI)—engaged in a highly targeted campaign to encourage the defection of Iraqi government and military officials with the technical skills and know-how to enhance its capabilities. For example, from 2004 onwards, it actively sought out those with explosives expertise to support its rocket and IED manufacturing activities, eventually leading to establishing a specific department for training purposes.

Fast forward several years, and throughout Nineveh and Anbar provinces, defection and reintegration were vital for the movement’s rebuilding in the aftermath of the group’s near decimation by the U.S. surge and Sunni Awakening (sahwa). Indeed, the Islamic State launched its own jihadi “awakening” units—mainly consisting of what could be described as defectors from tribes that had previously turned against the group—to lay the foundations for launching its guerrilla offensive after the withdrawal of U.S. forces in 2011.

Like government reintegration programs, prisons are also prioritized in the Islamic State’s approach to defection and reintegration. The prison folklore that often features in Islamic State propaganda promotes the heroics of its imprisoned leaders and the recruitment and integration of prisoners, particularly during “breaking the walls” campaigns. The Islamic State’s prison programs have always been connected to Al M’had Al Shar’i (Shari’a Institute). This includes within the Islamic State’s own prisons, where rehabilitation requires time spent in the Shari’a Institute to prove that one has been rehabilitated. Processing in the Sharia Institute is followed by an interview conducted by the relevant Shari’a Judge and post-repentance monitoring.

An Islamic State Tawba official reviews the forms of newly-submitted repentants during a defections and reintegration campaign. Photo: Al Furqan Media, "Clanging of Swords 4," May 2014.

As the Islamic State advanced its approach to defection and reintegration, information and intelligence collection were vital for providing the evidence base for its activities. Such efforts preceded its capture of major cities like Raqqa and Mosul in 2014. For example, a report produced by the Islamic State’s intelligence apparatus and assessed by one of the authors contained a list of government personnel working in Nineveh province, suggesting the details had been collected from 2006 to just before the fall of Mosul in 2014. The Islamic State’s information and intelligence gathering became increasingly sophisticated with the time, resources, and access to databases that controlling entire cities afforded them. This information was then used to improve strategies aimed at communities and individuals, from security and military personnel to labor and administration workers. Certain professions, such as those with chemical weapons manufacturing, military expertise, engineering, and scientific experience, were especially prized.

Its most systematic approach to defection and reintegration characterized the period of its greatest conventional successes. In the first few days of its capture of Mosul, the Islamic State established its Tawba (repentance) center, which called for anyone who worked with the government to come to repent. Through this system, many Mosulis were integrated into the Islamic State. The Tribal Affairs Diwan (administration) focused on reintegrating tribes into the group’s ranks in exchange for protection and socioeconomic and political opportunities. In Iraq, these activities happened all over Nineveh and Anbar provinces. The Islamic State’s defection and reintegration strategies became so institutionalized that even the Da’wah administration established programs for rehabilitating and reintegrating defectors, sinners, and converts. Alongside the work of the Shari’a Institute, these programs emerged as critical spaces for rehabilitating defectors who would engage in training programs followed by exams to prove to the Islamic State that they had been rehabilitated.

The Islamic State simultaneously threatened violence while offering protection from the violence of others as a powerful incentive for defectors to seek pardons. It offered those who sought to leave the ranks of its enemies full protection under the Islamic State. Along with protection, the group’s propaganda highlighted opportunities to earn a living and contribute to establishing the caliphate. Amnesty windows were offered by the Islamic State as fleeting opportunities for redemption after one’s safety would not be guaranteed.

However, not everyone was eligible to defect and reintegrate. In many cases, the Islamic State used the execution of defected professionals and government employees as a tool to terrorize tribes to force them to reintegrate within its system. For example, Colonel Isa Osman, head of the Emergency Regiment of the Local Police of Mosul, was publicly executed by the group in Mosul to demonstrate that some people were irredeemable and that those with a chance to be pardoned should take it.

Nonetheless, the Islamic State has demonstrated a willingness to be pragmatic even when it comes to the irredeemable. When recruitment of certain professions or just general manpower was needed, the group would often allow individuals and groups to be rehabilitated and reintegrated into their ranks that had previously been blocked.

A scene from inside the Islamic Court of Shari'a in Mosul. Photo: “Granting Justice to the People in the Courts of the Islamic State,” ISIS propaganda video produced in Mosul.

A Competition for Hearts, Minds, & Stomachs

Defection and reintegration efforts are once again crucial to the Islamic State as it seeks to rebuild after the territorial collapse of its caliphate. Its past and present information and intelligence collection activities will help to inform the approaches it adopts to draw a new generation away from government and civil society and into its perpetual wars. The Islamic State posture to be strategic opportunists leaves it poised to exploit vulnerabilities as they arise, and the lack of understanding about how the group uses defection and reintegration strategies is one such vulnerability. Beyond Iraq and Syria, the Islamic State has exported its defector and reintegration strategies across its global affiliates from Africa and the Middle East to Asia.

In those same areas of Islamic State activities, government and civil society are scrambling with their own defector and reintegration programs. Peace and P/CVE practitioners looking to hollow the ranks of the Islamic State and its supporters will need to understand the group’s approach to defection and reintegration. This is a competition for not only the hearts and minds, but the stomachs of communities that may span a demographic and socioeconomic spectrum. Psychosocial and ideological programs are always going to be important, but they are inevitably hollow if security, livelihood, and basic services are wanting.