IN THE MONTH since the Islamic State announced that it has a new caliph, pledges of allegiance (bay’ah) to Abu al-Hasan al-Hashimi al-Qurashi have flooded in from its provinces across the Middle East, Africa, and Asia. Given the devastating losses the movement has suffered in recent years, it would be easy to dismiss its bay’ah campaign as simply desperate propaganda. It should not be so easily dismissed. From the Islamic State’s perspective, these pledges are designed to project its leader as another in a succession of authoritative figures with the religious and military experience to be caliph. For its affiliates, it is a public recognition of that authority and the drawing of battlelines with its local rivals.

From a policy perspective, the Islamic State’s bay’ah campaign is also a timely reminder of the persistent global jihadist threat. Numerous Islamic State affiliates are operating in some of the world’s most fragile corners, many of which are also positioned on vital geopolitical fault lines that have significant implications for regional stability. With Russia and China challenging international norms, allies, and strategic interests in multiple theaters, Western nations are understandably focused on great power competition. In this period of re-posturing, it is vital for policymakers to understand that counterterrorism objectives, especially in support of weaker allies, are complementary to great power competition objectives.

Leadership Succession & Global Expansion

The Islamic State’s globalization is a relatively recent development in the movement’s history. Abu Bakr al-Baghdadi was not only the movement’s first caliph, but he oversaw its formal transnational spread beginning with Syria in 2013. When al-Baghdadi was killed in 2019, the Islamic State’s global affiliates responded by pledging allegiance to his successor, Abu Ibrahim al-Hashimi al-Qurashi. The reign of the “canary caliph” was the briefest of the movement’s top leaders, and he was killed during a U.S. Special Forces raid on February 3, 2022. According to an Al Naba editorial published on March 17, 2022, Abu Al-Hassan was appointed as the new caliph the day after Abu Ibrahim’s death.

Regardless, it took over a month before the Islamic State publicly announced its new leader on March 10, 2022. Within a week, the Islamic State’s media units had published two dozen photo reports from twelve provinces. On March 13, 2022, the Islamic State commenced its Jihad of the Believers Continues video series beginning with Wilayat al-Sham. Earlier this month, it released the eleventh video in the series featuring Filipino members of its East Asia province pledging to the new caliph.

The Islamic State’s bay’ah campaigns are a crucial component of its leadership succession practices. With its inner circle having appointed a successor as caliph, its members are then expected to pledge to the new leader as a public recognition of their authority. Just as formal affiliation requires groups to pledge to the caliph, this leader-specific pledge must be renewed with a new leader. After all, a leader’s authority requires recognition by the membership as a demonstration of its credibility and acceptance. The Islamic State’s global affiliates are renewing not just their commitment to the leader, but to the Islamic State’s ideology and strategy.

The Propaganda Battle Within the Global Jihad

Like so much of the Islamic State’s propaganda activities, the bay’ah campaign has multiple objectives. It is a globally synchronized propaganda campaign designed to project the authority of the new leader, the credibility of his position as caliph, and the global reach of the Islamic State. By pledging, global affiliates publicly renew their loyalty and are guaranteed to be featured by the Islamic State’s central media units. At the local level, the pledges also renew the battlelines between Islamic State affiliates and their local rivals. This is particularly important in locations where al-Qaida aligned groups had previously pledged to Osama Bin Laden only for breakaways to align themselves with the Islamic State after 2014.

Also crucial is the rivalry between the Islamic State and al-Qaida for the position of flagship of the global jihad. The Islamic State’s latest pledge campaign comes less than a year after the Taliban’s victory in Afghanistan somewhat rejuvenated al-Qaida stocks in the global jihadist milieu. Which side of the al-Qaida versus Islamic State fence a particular jihadist group sits was a reliable predictor for how they responded to the Taliban’s resurgence. After all, as far as Bin Laden and by extension al-Qaida were concerned, it was the Taliban’s Mullah Omar who should be considered Amir al-Mu’minin (Commander of the Faithful). The Taliban’s victory led some jihadists, for example in Indonesia, to call for Muslims to pledge bay’ah to the Taliban. The Taliban’s military successes last year gave a boost to al-Qaida’s brand and its more gradualist approach (at least compared to the Islamic State) for establishing and declaring an Islamic State.

The State of the Caliphate

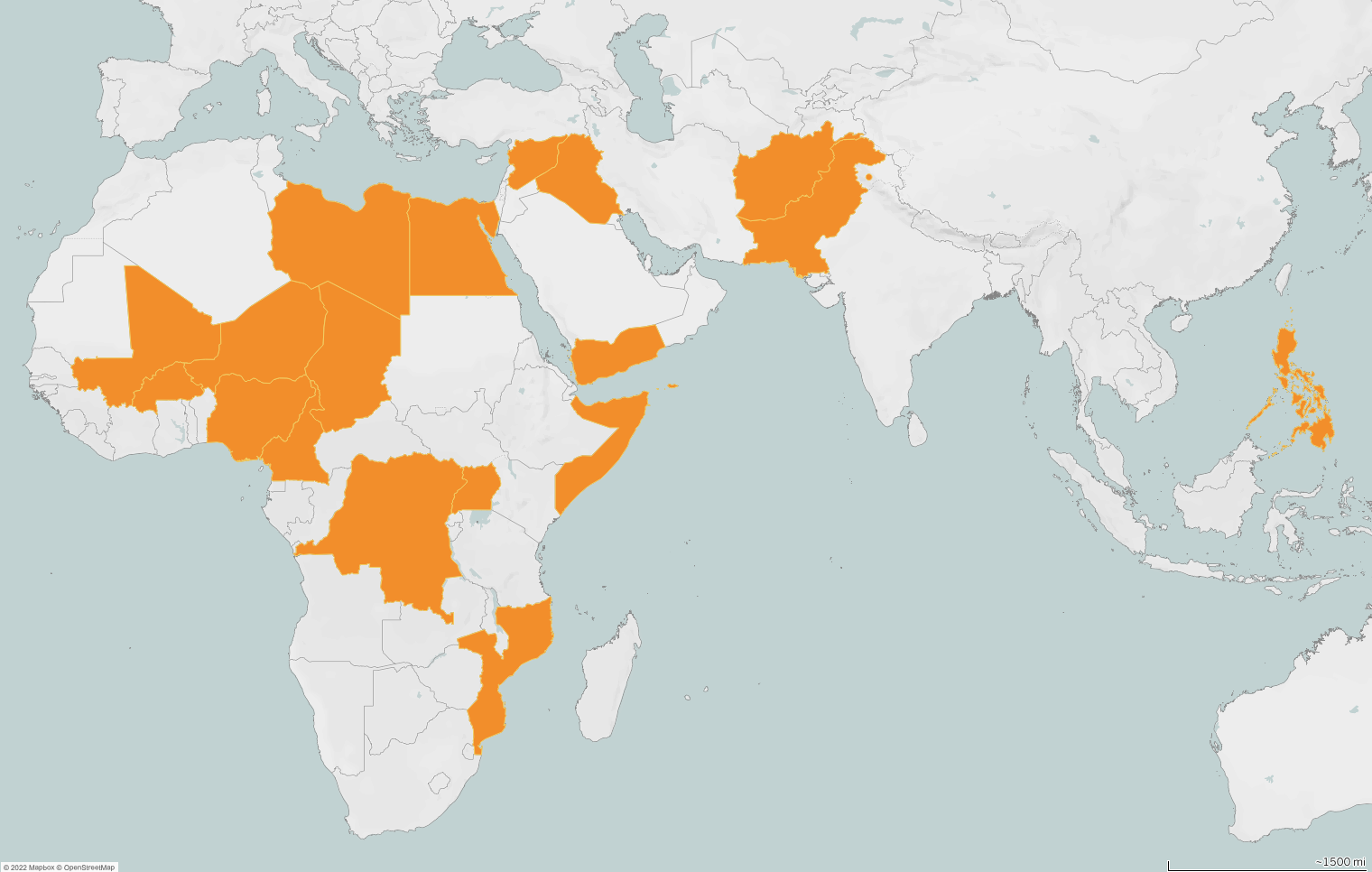

Within days of the public announcement, pledges to the new caliph emerged from Iraq and Syria to Nigeria, the Congo, and the Philippines. Trace the locations of the Islamic State’s pledge campaign on a map and many of its affiliates are positioned along crucial geopolitical fault-lines of regional instability. The Islamic State’s global network of affiliates is even more expansive than it was during the height of the so-called ‘caliphate’ in 2014-2015. The threat posed by some of these affiliates is comparatively reduced, but all remain poised to leverage operational opportunities, apply the Islamic State’s strategic method, and exploit distracted adversaries.

Country Locations of New Islamic State Pledges

The Middle East

In the Middle East, pledges have rolled in primarily across the Islamic State’s traditional heartlands of Iraq and Syria. Networks from Anbar, Diyala, Kirkuk, Salah al-Din, Nineveh, and other provinces all swore their allegiance to the new caliph within days of his announced succession. Their pledges were made shortly after a major Islamic State assault on al-Sina’a prison in northeast Syria late this January, which left hundreds dead after U.S. and British special forces rushed to support the Syrian Democratic Forces (SDF) and regain control. The assault is the latest in a long campaign of attacks stretching back to the liberation of ISIS’s last territorial holdings in March 2019. Since then, the group has carried out nearly 5,000 attacks across Iraq and Syria prior to the attempted prison break. According to recent UN estimates, the Islamic State maintains “between 6,000 and 10,000 fighters across both countries, where it is forming cells and training operatives to launch attacks.”

Numerous and active, the Islamic State’s networks across its Iraq and Syria heartlands are eyeing a future resurgence. And their targets are vulnerable. Cities like Mosul continue to rebuild and reclaim their cultural heritage, and so many communities who suffered under the Islamic State’s campaign of terror remain shattered and struggle to find justice years later, including the Yazidi population. Tens of thousands of individuals remain in SDF and coalition camps like al-Hawl, where the Islamic State is reported to have reinstated its youth indoctrination campaign, “Cubs of the Caliphate.”

To be sure, recent U.S. successes like the raid against al-Qurayshi, comparatively higher rates of repatriation of American foreign fighters and their families, and the high-profile conviction of notorious ISIS Beatle El Shafee Elsheikh are laudable. But without addressing key issues like broader repatriation efforts, SDF partner capacities, and community resilience in major urban areas like Mosul, the situation remains vulnerable to a resurgent Islamic State. All the while, other regional competitors like Iran—not to mention great power competitors like Russia—will continue leveraging proxies for influence, strategic gains, and military supremacy under the pretense of security, no matter the cost to local populations and U.S. interests.

Africa

Pledges to the new caliph also arrived in short order from North, West, Central, and East Africa. Longstanding affiliates in Libya, Somalia, and the Sinai were among them, though Islamic State-linked operations in these countries have been relatively diminished in recent years. In West Africa, however, deft management from IS-core to guide Islamic State in the Greater Sahara (ISGS) through the loss of its top leader, Adnan Abu Walid al-Sahraoui, appears to have paid dividends. The group’s new leader, Abdul Bara al-Sahraoui, reaffirmed his predecessor’s allegiance by pledging to the new caliph, and reoriented the group’s posture to increase attacks on civilians in the Liptako Gourma region, which borders Niger, Mali, and Burkina Faso. These attacks have forced thousands of locals to flee, and only added to the 2,000,000+ internally displaced persons in the region. Nearby in the Lake Chad region, the death of Abubakar Shekau has strengthened the Islamic State West Africa Province’s (ISWAP) position. ISWAP has not only enjoyed limited success in integrating some Boko Haram members despite a tricky history, but also expanded its operations beyond Nigeria to the country’s Lake Chad neighbors.

Further east, the threat posed by Islamic State’s Central Africa Province (ISCAP) is metastasizing. The Allied Democratic

Forces (ADF), an ISCAP component group operating in the Democratic Republic of the Congo and Uganda, has ramped up attack campaigns against both civilians and security forces. What’s more, ADF forces have expanded beyond North Kivu and into Ituri province. Several hundred miles to the southeast, ISCAP forces in Mozambique’s Cabo Delgado Province—led by Ahl al-Sunna wal-Jamaa’ (ASWJ) leader Abu Yasir Hassan—continue attacks despite recent setbacks. While analysts and governments still debate whether an ASWJ-Islamic State connection even exists, the group is entrenched for a protracted struggle.

The U.S. and its partners face a host of challenges across the African continent. While Islamic State affiliates in some regions may be subdued, the broader movement has positioned itself for a long fight in multiple key regions. Attacks on civilians and security forces remain high, as do refugee and IDP numbers. Failure to provide counterterrorism assistance to current and potential partners can not only offer openings for Islamic State affiliates to exploit; as Daniel Byman recently argued, they also create vacuums that great power competitors like China, Russia, and lesser powers seek to fill. To some extent, Russia has already attempted to do so through its mercenary Wagner Group.

Asia

In Asia, Islamic State affiliates in Afghanistan, Pakistan, Kashmir/India, and the Philippines all featured in the latest bay’ah campaign. Despite low levels of attacks in 2022, the centralization of the Islamic State Hind Province’s (ISHP, Kashmir/India) various media groups and channels into a single outlet shows growing coordination, and could signal a more aggressive attacks campaign in the near future. Islamic State Pakistan Province (ISPP, Pakistan excluding Khyber-Pakhtunkhwa province) continues to position itself as the main jihadist alternative to a much stronger Pakistani Taliban (TTP), which it decries as apostates, especially during periods of negotiations between the TTP and Pakistani government. Both ISHP and ISPP seek to exploit geopolitical tensions and increase support bases in their respective regions, and may enjoy expanded footholds if domestic unrest deepens and regional security cooperation fails.

The most formidable affiliate in the region, however, is Islamic State Khurasan Province (ISKP, Afghanistan and Pakistan’s Khyber-Pakhtunkhwa province), which has firmly established itself as the main jihadist rejectionist force to Taliban rule in Afghanistan. ISKP rallied and revamped attack operations under its current leader, Sanaullah Ghafari, after years of sustained counterterrorism pressure, and attacks against civilian minorities like the Hazaras—as well as Taliban personnel—have just resumed after a winter lull. A core pillar of ISKP’s resurgence strategy has been leveraging its diverse militant base, offering a platform for Uyghur, Uzbek, Pakistani, and other militants to pursue their strategic goals. Attacks like the recently-claimed rocket assault on an Uzbek base by an ISKP militant not only exacerbate Taliban relations with neighboring countries, but flaunt Taliban failures on basic security guarantees.

In southeast Asia, Islamic State East Asia Province (ISEAP) maintains a fragmented and weakened presence in the southern Philippine region of Mindanao years after the 2017 Siege of Marawi. Given the highly-localized roots of IS-linked groups in the region, much of the effort to prevent a resurgent ISEAP presence and safeguard broader peace efforts in Mindanao will need to be directed through soft measures as well as kinetic ones. This presents the U.S. with a unique opportunity for strengthened security partnership and broader cooperation with the Philippines.

In Asia just as in Africa, the status of multiple Islamic State affiliates is in flux but generally on the rise. With IS-core eyeing expanded operations not only in official provinces like ISKP but also potentially in countries with pro-Islamic State groups like Thailand and Myanmar, the necessity for counterterrorism vigilance remains. At the same time, strategic competitors continue to leverage local proxies and regimes for influence and to counterbalance perceived threats. This comes at direct cost to U.S. interests, partnerships, and efforts to lead the international community on basic democracy and human rights benchmarks. As with Africa, the need for the U.S. to strengthen and expand on existing counterterrorism partnerships in Central, South, and Southeast Asia is evident.

Counterterrorism in an Age of Great Power Competition

As Abu al-Hasan takes stock of his new position, he faces the challenge of re-harnessing the Islamic State’s global enterprise after the brief rule of his predecessor, Abu Ibrahim. That so many longstanding and relatively newer affiliates pledged allegiance in rapid order is proof that the Islamic State enterprise still inspires loyalty around the world. With the movement transitioning out of the delicate leadership succession period, Islamic State affiliates from the Middle East to Africa to Asia stand ready to pursue its strategic method anew.

Persistent and resurgent Islamic State threats along multiple geopolitical fault lines merit continued monitoring. They also demand that U.S. and Western partnerships with local allies be reinforced and expanded. Rather than deprioritize counterterrorism objectives in the face of great power competition, the U.S. and its partners need to recognize that counterterrorism objectives can, and must, complement great power competition. Across the globe, Western counterterrorism goals of containing and degrading jihadist adversaries can strengthen security partnerships with local allies, bolster partners’ long-term capacities, rebalance hard and soft approaches, and limit competitors’ military influence in key geopolitical regions all while expanding Western partnerships and influence. At the same time, a more competitive Western counterterrorism posture can shape the very rule-of-law promotion, human rights reform, and resilience to anti-democratic influence operations that will be central to protecting and strengthening democracies under assault from state and non-state actors worldwide.

If the West cannot cohere counterterrorism efforts to a new age of great power competition, it is strategic competitors and jihadist adversaries themselves who will step in to fill the void. If they are allowed to succeed, then failures beyond the disastrous withdrawal from Afghanistan will soon follow.