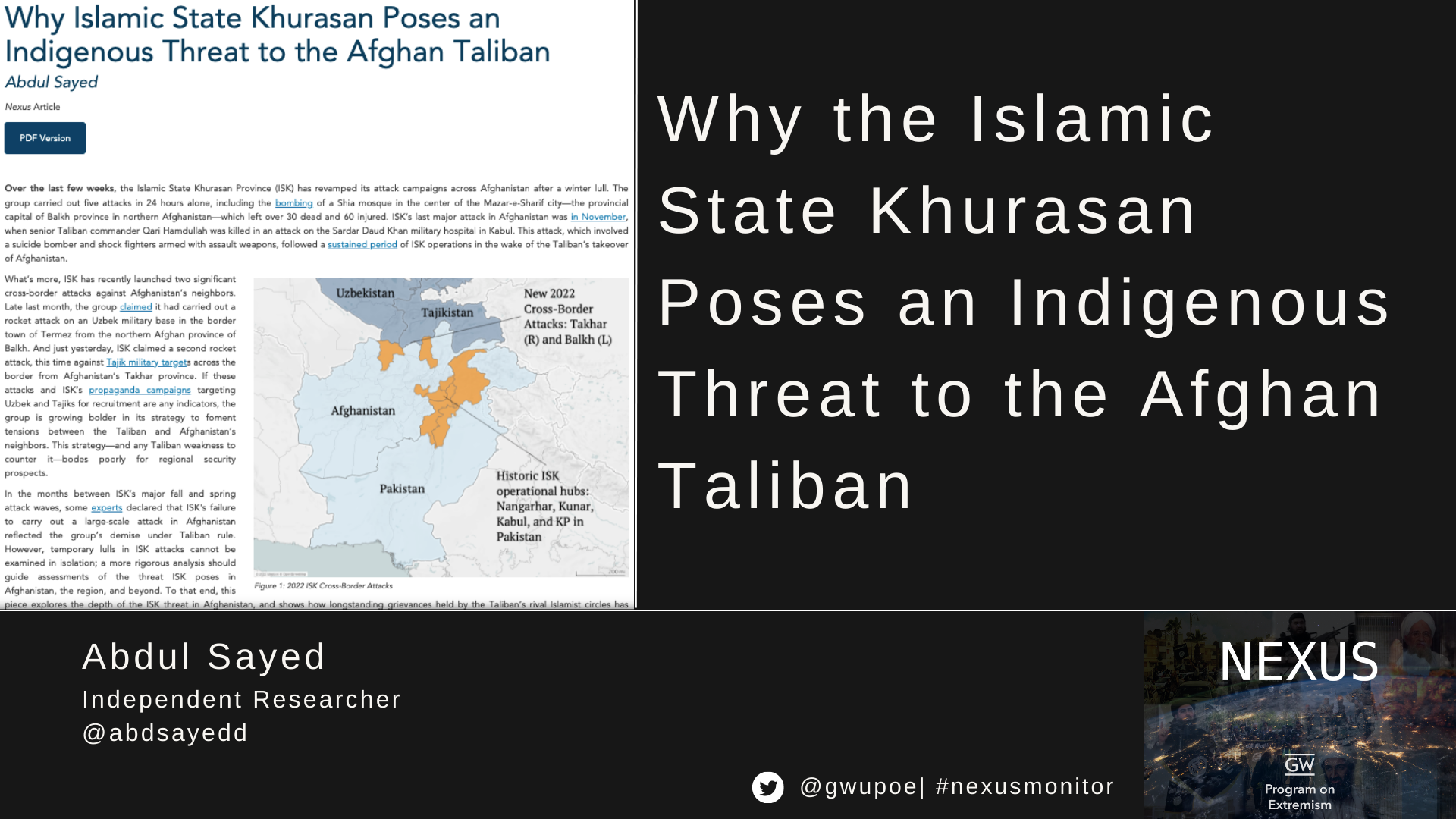

OVER THE LAST FEW WEEKS, the Islamic State Khurasan Province (ISK) has revamped its attack campaigns across Afghanistan after a winter lull. The group carried out five attacks in 24 hours alone, including the bombing of a Shia mosque in the center of the Mazar-e-Sharif city—the provincial capital of Balkh province in northern Afghanistan—which left over 30 dead and 60 injured. ISK’s last major attack in Afghanistan was in November, when senior Taliban commander Qari Hamdullah was killed in an attack on the Sardar Daud Khan military hospital in Kabul. This attack, which involved a suicide bomber and shock fighters armed with assault weapons, followed a sustained period of ISK operations in the wake of the Taliban’s takeover of Afghanistan.

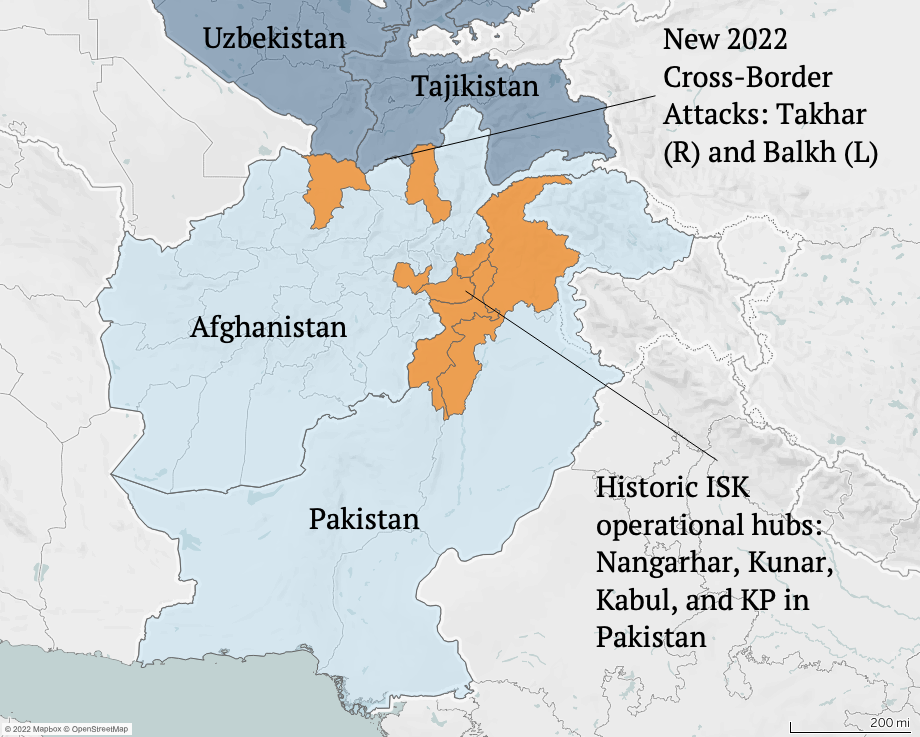

2022 ISK Cross-Border Attacks

What’s more, ISK has recently launched two significant cross-border attacks against Afghanistan’s neighbors. Late last month, the group claimed it had carried out a rocket attack on an Uzbek military base in the border town of Termez from the northern Afghan province of Balkh. And just yesterday, ISK claimed a second rocket attack, this time against Tajik military targets across the border from Afghanistan’s Takhar province. If these attacks and ISK’s propaganda campaigns targeting Uzbek and Tajiks for recruitment are any indicators, the group is growing bolder in its strategy to foment tensions between the Taliban and Afghanistan’s neighbors. This strategy—and any Taliban weakness to counter it—bodes poorly for regional security prospects.

In the months between ISK’s major fall and spring attack waves, some experts declared that ISK's failure to carry out a large-scale attack in Afghanistan reflected the group’s demise under Taliban rule. However, temporary lulls in ISK attacks cannot be examined in isolation; a more rigorous analysis should guide assessments of the threat ISK poses in Afghanistan, the region, and beyond. To that end, this piece explores the depth of the ISK threat in Afghanistan, and shows how longstanding grievances held by the Taliban’s rival Islamist circles has provided a strong base for ISK in Afghanistan today.

ISK’s Rise and Intra-Sunni Jihadist Fault Lines

A senior commander of the Tehrik-e Taliban Pakistan (TTP), Hafiz Saeed Khan, founded the Islamic State Khurasan (ISK) in early January 2015. As the group’s first governor, he promised anti-state Pakistani militants that ISK would intensify the jihadist war in Pakistan. ISK soon found a home in Afghanistan, but following major counterterrorism operations against many of the group’s founding Pakistani members, Afghan militants quickly came to dominate its rank and file. These militants were critical of the Afghan Taliban due to longstanding religious and political biases. Fearful of the burgeoning ISK threat, the Afghan Taliban leadership publicly requested Islamic State Core leadership in Iraq and Syria to avoid providing rival militants a franchise in Afghanistan, arguing that the result would be intra-jihadist bloodshed.

The Taliban’s fear of ISK’s rise was both well calculated and rooted in intra-Sunni jihadist differences spanning back to the Taliban’s rise in the early 1990s. Fault lines in the Sunni jihadist movement in Afghanistan have since provided fertile grounds for pro-Islamic State expansion in the region. With the Taliban now in power, these intra-Sunni jihadist fault lines are even more important to study and understand. They show how ISK is an indigenous threat to the Afghan Taliban today, one with serious security implications for the region and for the broader international community.

ISK’s expansion in Afghanistan is due in large part to the platform provided by the Taliban's rival Afghan jihadists. These included religious and political rivals, mainly Afghan Salafists and militants affiliated with Hezb-e-Islami Gulbuddin (HIG)— a major offshoot of the Muslim Brotherhood in Afghanistan. These groups still lament the Taliban victimizing them after consolidating power in the 1990s and turning Afghanistan into a totalitarian state adherent to the traditionalist Deobandi movement, a particular sect of the Hanafi school within Sunnism. While Salafists and HIG both fall under the umbrella of Sunni Islam, they maintain stark doctrinal and political differences with the Taliban’s Deobandi practices.

Although themselves victims of Taliban policies, these groups had foundational roles in the post-9/11 insurgency in Afghanistan. Besides expelling the “invader infidels”, they hoped they would get an equal share in the future Islamist Afghanistan alongside the Taliban. After the U.S.-led coalition destroyed their regime and scattered their fighters, the Taliban had to restart their insurgency with a guerilla strategy for a new war in Afghanistan. Part of that strategy hinged on the Taliban eliminating groups and individuals from 2007-2008 onwards that posed a threat to their monopoly on power. This frustrated the Taliban’s rival Islamists, who claimed an equal share in fighting against the coalition and who had similar power ambitions to the Taliban, especially the region’s Salafists and HIG-affiliated militants. Years later, ISK would provide these parties a sophisticated platform for settling scores with the Taliban.

The Taliban and Afghanistan's Salafists

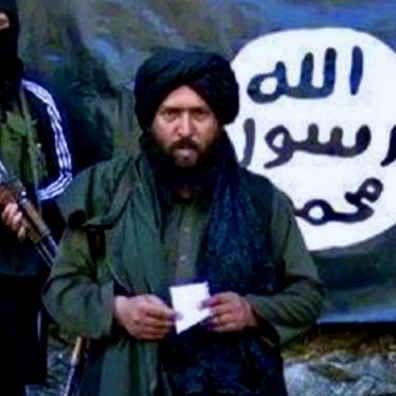

JLQWS founder Jameel ur Rehman provides a sermon to his followers.

Salafism emerged as a new variant of Sunni Islam in Afghanistan with the arrival of Arab foreign fighters to support the Afghan militants’ war against the Soviet invasion in the early 1980s. Salafists dominated the northeastern province of Kunar after a prominent Afghan jihadist leader, Shaikh Jameel ur Rehman a.k.a. Mulawi Hussain, embraced Salafism under the influence of its Middle Eastern proponents. Hussain belonged to the Panjpir sect of Hanafi Islam, and was the provincial emir of HIG for Kunar province. He founded the first ever Salafi-jihadist party of Afghanistan, Jamat Lil Quran Wal Sunna (JLQWS).

Hussain was a charismatic jihadist leader who had widespread influence among Afghan jihadists, particularly in his native province and its surroundings. He started preaching Salafism and held a leading role in fighting against the invading Soviet force and its supported Afghan regime in Kabul. Kunar soon turned into a Salafi-dominated province with his efforts. Hussain established a Salafist state in Kunar, which was the first Salafist proto-state in modern history.

However, HIG soon moved to thwart the Salafis’ proto-state project, which HIG saw as upsetting the party’s hegemony over the Pashtun provinces, particularly in Eastern Afghanistan including Kunar. Hussain was assassinated in a targeted attack in August 1991, hardly a year after establishing his Salafist state in Kunar, which dissolved with his murder.

Due to these major setbacks, Afghan Salafists centered their focus predominantly on non-militant approaches for propagating Salafism in Afghanistan and in its adjacent Pashtun belt of Pakistan. They established seminaries that produced hundreds of graduates steeped in Salafist doctrine every year. These Salafist graduates spread across Afghanistan and Afghan refugee camps in Pakistan to preach Salafism. Above all, wealthy Salafist donors from the Middle East supported charity projects for needy Afghans, which further accelerated the expansion of Salafism among the Afghan population.

With the Taliban's accession to power in the early 1990s, Salafists faced a challenging era in Afghanistan. While Salafism had made inroads out of Kunar and into the provinces of Nangarhar, Laghman, and even the capital Kabul, Salafists faced stringent Taliban restrictions in these areas. These restrictions were mainly the product of sectarian differences, aimed to limit Salafism’s spread in Afghanistan. Several Salafists seminaries were closed, and books were confiscated. A delegation of Afghan Salafists met the Taliban leadership in Kabul, including Prime Minister Mullah Muhammad Rabbani, but to no avail.[1]

U.S. Forces on assignment in Kunar province. Photo: US Army

Among the Afghan Salafist scholars who suffered under these Taliban restrictions were Shaikh Abu Obaidullah Mutawakil in Kabul and Shaikh Abdul Rahim Muslim Dost in Nangarhar. Both supported the post-9/11 Taliban insurgency in Afghanistan, and would later become notable proponents of ISK’s efforts in Afghanistan. Dost had an influential role in laying ISK’s foundation in the Af-Pak region, and is regarded by many to be the core ISK founder in Afghanistan. Mutawakil was respected as the senior-most Afghan Salafist scholar and a top supporter of ISK before being brutally killed in Kabul after the Taliban’s takeover in August. Dozens of his students joined ISK, including ISK's current top leader, Dr. Shahab al-Muhajir.

The U.S. invasion of Afghanistan in 2001 provided Afghan Salafists a renewed militant jihad opportunity for the greater religious duty of expelling invading apostates from the homeland. A senior Afghan Salafist interviewed by this author stated that influential Afghan Salafist leaders held a secret meeting in early 2002 in the north-western provincial capital of Peshawar, Pakistan, to organize a militant resistance against the U.S. and allied forces in Afghanistan.[2] They agreed that although the Taliban regime had oppressed them, they held equal responsibility to the Taliban to fight against the invaders. Sources who attended this meeting confirmed to the author that the convener of the meeting was Haji Hayat Ullah, nephew and military successor to Mulawi Hussain (Shaikh Jameel).[3]

Moreover, post-9/11 anti-U.S. public sentiments within Islamist circles across Afghanistan and Pakistan emboldened Afghan Salafists to wage militant jihad once again. Fanning the flames were influential Salafi-jihadists in the ranks of al-Qaeda and allied foreign militant groups, who played an instrumental role in pushing Afghan Salafists towards the greater jihad against the U.S. Al-Qaeda and allied Arab jihadists focused on mobilizing local allies for a joint insurgency with the Taliban against the U.S. and its allies. Thus, with al-Qaeda's economic and military support, the Salafists strengthened their post-9/11 insurgency against the U.S., resulting in heavy casualties to U.S. forces. Once again, the Salafist-dominated Kunar province cemented its reputation as the hardest place for U.S. forces in Afghanistan, which even President Joe Biden labeled the "gates of hell".

The Taliban and Hezb-e-Islami Gulbuddin (HIG)

Apart from Afghan Salafists, HIG is another major Taliban rival jihadist group that played a founding role in the post-9/11 jihadist war against the U.S. and its allies. HIG was the largest Afghan jihadist party before the Taliban's emergence, dominating Afghanistan’s Pashtun majority provinces that the Taliban first captured during their emergence in the 1990s. HIG was seen as Pakistan’s primary proxy in Afghanistan just as the Taliban would later be regarded. Unlike the Taliban, however, HIG was a founding party of the Muslim Brotherhood in Afghanistan and held deep religio-political doctrinal differences with the Taliban. Because of these factors, HIG was one of the Taliban’s most critical rivals since the latter’s beginnings.

Like the Taliban, HIG declared war against the U.S. and allied forces, a sacred religious duty for every Afghan. In fact, Al-Qaeda and its allied foreign jihadist commanders played a central role in connecting HIG to the jihadist war against the U.S. and its allies after 9/11. These included post-9/11 senior al-Qaeda commanders like Abdul Hadi Iraqi, who were affiliated with HIG before the Taliban’s emergence in early 1990s. HIG commanders even sheltered Osama Bin Laden alongside senior group leaders including Ayman al-Zawahiri in Kunar after they escaped U.S. targeting operations on the Tora Bora mountains in 2001. With al-Qaeda’s support, HIG affiliated militants played a central role in the insurgency and conducting terrorist attacks in Afghanistan, as well as running a parallel militant network in Afghanistan.

During the Taliban’s push for consolidation after 2007, HIG fighters were forced either to join the Taliban’s ranks or lay down their arms. This resulted in fighting between both sides in provinces like Baghlan, Wardag, and elsewhere. In the process, the Taliban almost succeeded in neutralizing the entire HIG militant network in Afghanistan. This was the reason that HIG emir Gulbuddin Hekmatyar publicly called on its fighters to support ISK in its war against the Taliban in 2015, referencing the Taliban’s oppression against HIG in the past.

Salafi-jihadists in Al-Qaeda and the TTP Rebel against the Taliban

Like Afghan Salafists, Salafists from Pakistan’s Pashtun belt bordering Afghanistan adopted militant jihad against the U.S. and its allies after the post-9/11 U.S. invasion. These Salafists became part of the Afghan Taliban-allied, anti-state Pakistani militant group– Tehrik-e Taliban Pakistan (TTP). Like the Afghan Taliban, the TTP also adhered to the Deobandi Hanafist school of thought. Unlike in the Afghan Taliban, however, Salafists enjoyed considerable freedom within the TTP. This was due to the TTP’s fluid organizational structure in which affiliated branches enjoyed significant independence.

Among the seven large tribal branches of the TTP, Orakzai and Bajaur had a significant presence of Salafists. These Salafists were extensions of the Salafist trend that started in Afghanistan under Mulawi Hussain’s leadership in the early 1980s. Thus, Salafists in the TTP’s ranks had close relations with Salafists in the Afghan Taliban. For example, prominent Afghan Salafists remained part of the Afghan Taliban insurgency after 9/11, like Dost and Saad Emirati, who had close relations with the TTP’s Orakzai chapter. Dost and Saad Emirati became founding ISK commanders when the TTP’s Orakzai chapter emir, Hafiz Saeed Khan, pledged allegiance to Abu Bakr al-Baghdadi and founded ISK.

Founding ISK governor (wali) Hafiz Saeed Khan in one of the group's propaganda releases.

Most of the al-Qaeda senior leadership who played a role in uniting the Taliban’s rival Afghan jihadists—particularly HIG and Salafist militants—for a joint armed jihad alongside the Taliban against the “invading infidels” were gradually killed in U.S. drone strikes from 2008 to 2014. This resulted in the rise of a new al-Qaeda leadership in the region that was dominated by hardliner Salafists. Some influential voices within this new al-Qaeda leadership soon objected to al-Qaeda policies and strategy in Khurasan. Among other matters, this included the group’s tolerance of Taliban and local militants’ theological beliefs and religious practices, which the Salafists consider deviances and innovations in religion. Nine of these al-Qaeda leaders comprised the first group of jihadist leadership from Khurasan that publicly announced allegiance to soon-to-be ISIS caliph, Abu Bakar al-Baghdadi, in March 2014. The published accounts of the three senior figures of this group—Abu Huda Sudani, Abu Ta'ir Urdani, and Abu Ubaydah Lubnani—point out that their major grievance against top al-Qaeda leader Ayman al-Zawahiri was his prioritizing the Hanafi creed over Salafism, which they believed violated Salafist principles. As a result, these leaders started a regional recruitment campaign for al-Baghdadi before he declared the so-called ‘caliphate’ later that summer. Sudani, Urdani, and Lubnani succeeded in securing pledges of powerful Salafist military commanders in the region, like the TTP’s Orakzai chapter emir Hafiz Saeed Khan and the TTP’s spokesperson Shahidullah Shahid, alongside four other TTP commanders. The TTP’s Orakzai chapter controls large amounts of territory on the Pakistan side of the border, which served as a base for like-minded jihadists to gather and first establish ISK under Khan’s stewardship.

New Rulers, Same Old Policies

Within 48 hours of the Taliban’s takeover last summer, HIG chief Gulbadin Hikmatyar and the most influential Afghan Salafist scholar, Abu Ubaida Mutawakil, announced their support to Afghanistan’s new rulers. Hikmatyar labeled the Taliban takeover of Kabul the most peaceful regime change in recent Afghan history and called it a great victory for the country’s Islamists. During the chaos of the Taliban takeover, Mutawakil managed to escape from the Pul-i-Charkhi prison in Kabul, where he had been held for over two years for alleged links to ISK. He quickly issued a video message welcoming and congratulating the Taliban on its great Islamist victory. Mutawakil also told his supporters to support Taliban rule in the country. This one-sided relationship did not last long.

Taliban fighters abducted Mutawakil from his home in Kabul on August 28th and brutally killed him after severe torture. His beheaded body, burnt beyond recognition, was found on a roadside in Kabul on September 5th. Taliban spokesperson Zabihullah Mujahid denied his party's role in the murder, but he also failed to condemn this brutal killing. Mujahid promised an investigation would be launched into Mutawakil’s death, but no information has since been shared with the media. In an interview with this author, a close friend and colleague of Mutawakil blamed anti-Salafist sectarian elements within the Taliban for abducting him and carrying out this brutal killing.[4]

Just a few days after the Kabul takeover, Taliban fighters stormed the HIG central office in Kabul, blaming the group for sheltering ISK members.[5] Weeks later, the HIG’s youth wing leader, Ezatullah Mohib, was abducted and killed in Nangarhar. His dead body was found on a roadside in late October with a note alleging his support and links to ISK.[6] In the wake of the Taliban’s return to its anti-HIG discriminatory practices, HIG chief Hikmatyar blamed the Taliban for harassing, arresting, and killing his party members on false accusations, decrying these as “unwise policies” that would yield bad results for Taliban-HIG relationships.

Although these tensions have subsided somewhat in recent months (at least in media reporting), the Taliban have never let their Islamist rivals of the past feel at home under their rule. A delegation of senior Salafist leadership led by Shaikh Sardar Wali and Shaikh Ahmad Shah announced support for the Taliban during a gathering held by the Taliban intelligence and vice and virtue ministries in late October. These Salafists demanded that the Taliban end the arrest and killing of Salafist youth on false allegations of links with ISK. They lamented Taliban actions to counter ISK as creating misunderstandings between Afghanistan’s new rulers and their Salafist subjects. If the Taliban continues to alienate Afghanistan’s substantial Salafist community through discriminatory practices and extrajudicial killings, the result may be renewed splintering within the Taliban's rival Islamist circles that will only strengthen ISK’s war against the Taliban. With the arrival of ISK’s spring attacks campaign and widened recruitment and targeting efforts, it is vital to not let the group’s regional strategy detract from fundamentally local dynamics. ISK poses an indigenous threat to the Afghan Taliban, and neither the lessons of history nor the initial months of Taliban rule hold many promises for a peaceful and secure future.

Endnotes

[1] Author interview with sources based in Peshawar, Pakistan and Kunar, Afghanistan, in January 2022, conducted remotely.

[2] Author interview with sources based in Peshawar, Pakistan and Kunar, Afghanistan, in January 2022, conducted remotely.

[3] Ibid.

[4] Author interview with a Salafist scholar who was a close friend and colleague of Shaikh Abu Obaidullah Mutawakil, conducted remotely on September 5, 2021.

[5] Different sources in Kabul confirmed this incident to the author in separate interviews conducted remotely during September-November 2021.

[6] Ibid.