AT THE ONE-YEAR MARK of Taliban rule, al-Qaeda’s trajectory in Afghanistan remains a major concern. Al-Qaeda leader Ayman al-Zawahri’s presence in Kabul before his death in a U.S. drone strike suggests that the movement’s leadership continued to see Afghanistan as a preferred location for its political nerve center, as well as to continue leveraging longstanding relationships with the Taliban. Earlier in 2022, U.S. intelligence assessed that the Taliban were still maintaining ties with al-Qaeda’s senior leadership despite their stated commitments in the 2020 U.S.-Taliban Doha agreement to prevent international jihadists, including al-Qaeda, from using Afghan soil to threaten the United States and its allies. Then in June, CENTCOM chief Gen. Michael ‘Erik’ Kurilla noted that the U.S. military had detected new training camps in Afghanistan. When news broke publicly in August that al-Zawahri reportedly had been protected in a compound linked to Taliban Interior Minister Sirajuddin Haqqani, proof of al-Qaeda’s comfort in Taliban-ruled Afghanistan seemed all but certain.

Yet, the scandal of al-Zawahri’s discovery in Kabul falls short of the worst-case scenario of the Taliban’s return: a swift al-Qaeda expansion in the country, and an attack against U.S. interests and allies in the region or on the homeland. Today, al-Qaeda’s overt signature in Afghanistan remains limited. And when compared to the late 1990s—during which al-Qaeda built up a large-scale, highly visible infrastructure within a year of the Taliban’s takeover—no such overt activity has been reported in Afghanistan, at least for now. No major movement of foreign fighters into Afghanistan has been reported either, nor have the main al-Qaeda ideologues called for a grand migration, or “hijra”, to the Taliban’s emirate. There is also little to suggest that the U.S. government or other Western countries have detected any al-Qaeda plot linked to Afghanistan over the last year. For its part, the White House is observing that al-Zawahri’s move to Kabul was an anomalous event and al-Qaeda isn’t regrouping in Afghanistan.

What, then, accounts for the current threat trajectory of al-Qaeda in Afghanistan? What are the drivers and constraints of this threat? And to what extent can the current U.S. over-the-horizon counterterrorism strategy manage it?

The Taliban Calculus

Analysts are still struggling to understand who knew what about al-Zawahri’s presence within the Taliban. Indeed, most observers have limited visibility into the Taliban’s internal debate on al-Qaeda. Taliban interlocutors have describe the movement as split over the scope and limits of expansionist jihadist activity by groups based in Afghanistan. These interlocutors suggest that some Taliban leaders in Kabul want to focus on building strong state institutions with foreign aid money and, to that end, want to accommodate the concerns of the international community. These leaders seem to also spearhead the Taliban's public counterterrorism assurances to the international community.

But this constituency ultimately is unable to sway Taliban decision-making. The more important sub-group within the Taliban that appears to have the decisive vote on the most significant policy issues is not in Kabul but in Kandahar. And it is constituted by the Taliban supreme leader, Maulvi Hibatullah Akhundzada, and his inner circle of clerics.

In the last few months, Akhundzada has defied the conventional view that he is a reclusive southern “mullah” who offers spiritual guidance but no strong views on policy. Instead, he has gradually asserted more of his uncompromising vision over the Taliban movement. And that vision provides no indication that Akhundzada seeks to limit space for major jihadists like al-Qaeda in Afghanistan. In his most significant public speech at a recent conclave of Muslim scholars in Kabul, he leaned on the theme of a long, enduring ideological battle with the Western world:

“The infidels were not fighting us for land, for money and no other thing, except our ideology and faith… and they decided to suppress our ideology… and stop the jihad, ban the sharia… the fight still hasn't ended, it still exists. And it won't end until the day of judgement.”

In the same speech, he went on to claim that, “People are now waiting to see whether or not the objective of jihad is realized,” and reminded the audience of their obligation to the movement’s martyrs, which included his own son: “My innocent child sacrificed his life for the same objective.”

A recording of Akhundzada's remarks at a recent conclave of Muslim scholars in Kabul, released by Ariana News.

Beyond his rhetoric, there are indications that Akhundzada has instructed his followers to provide continued security for al-Qaeda members, and, according to one account relayed to the author,[1] he has ordered limits on discussion of al-Qaeda’s “bayah” or fealty to him. When major Taliban leaders have suggested concessions to the international community on al-Qaeda or counterterrorism in general, Akhundzada and his inner circle appear to have resisted. For example, Akhundzada appears to have stifled a proposal to limit jihadist groups inside Afghanistan,[2] in particular al-Qaeda, suggested by Mullah Abdul Ghani Baradar last year.

The Taliban also continue to decline opportunities to engage with the international community and demonstrate their intent to distance from al-Qaeda. For example, before the al-Zawahri strike, U.S. Special Envoy Tom West bemoaned that his dialogue with the Taliban on al-Qaeda remained challenging. In July, the government of Uzbekistan sought to organize an international conference, one they hoped could lead to tangible counterterrorism assurances and a clear Taliban break from al-Qaeda. The Uzbek government initially seemed confident of securing such an agreement, but in the end the Taliban appear to have refused further discussion on al-Qaeda.

If Akhundzada, the Taliban’s current supreme leader, is one of the main sources of support for jihadists in Afghanistan (and al-Qaeda in particular), can he be coaxed to change his position? Current dynamics suggest that is unlikely. In the aftermath of the al-Zawahri strike, the Taliban have come under intense pressure from their internal constituents and various jihadist allies in the country. Sirajuddin Haqqani, in particular, has been targeted by various factions within the Taliban. Some are questioning him for failing to protect al-Zawahri. Others feel revolted at America’s violation of Afghan sovereignty and non-aggression commitments in the Doha agreement. Akhundzada may be feeling the pressure in the current environment, but nothing suggests that he is moving away from al-Qaeda in any visible way. In fact, he has only deepened his support for Sirajuddin Haqqani against the many criticisms being levied, and hit back by not only condemning the United States for carrying out the strike, but also threatened Afghanistan’s neighbors against facilitating future strikes, most likely a warning directed at Pakistan.

Where Does Al-Zawahri’s Death Leave Al-Qaeda?

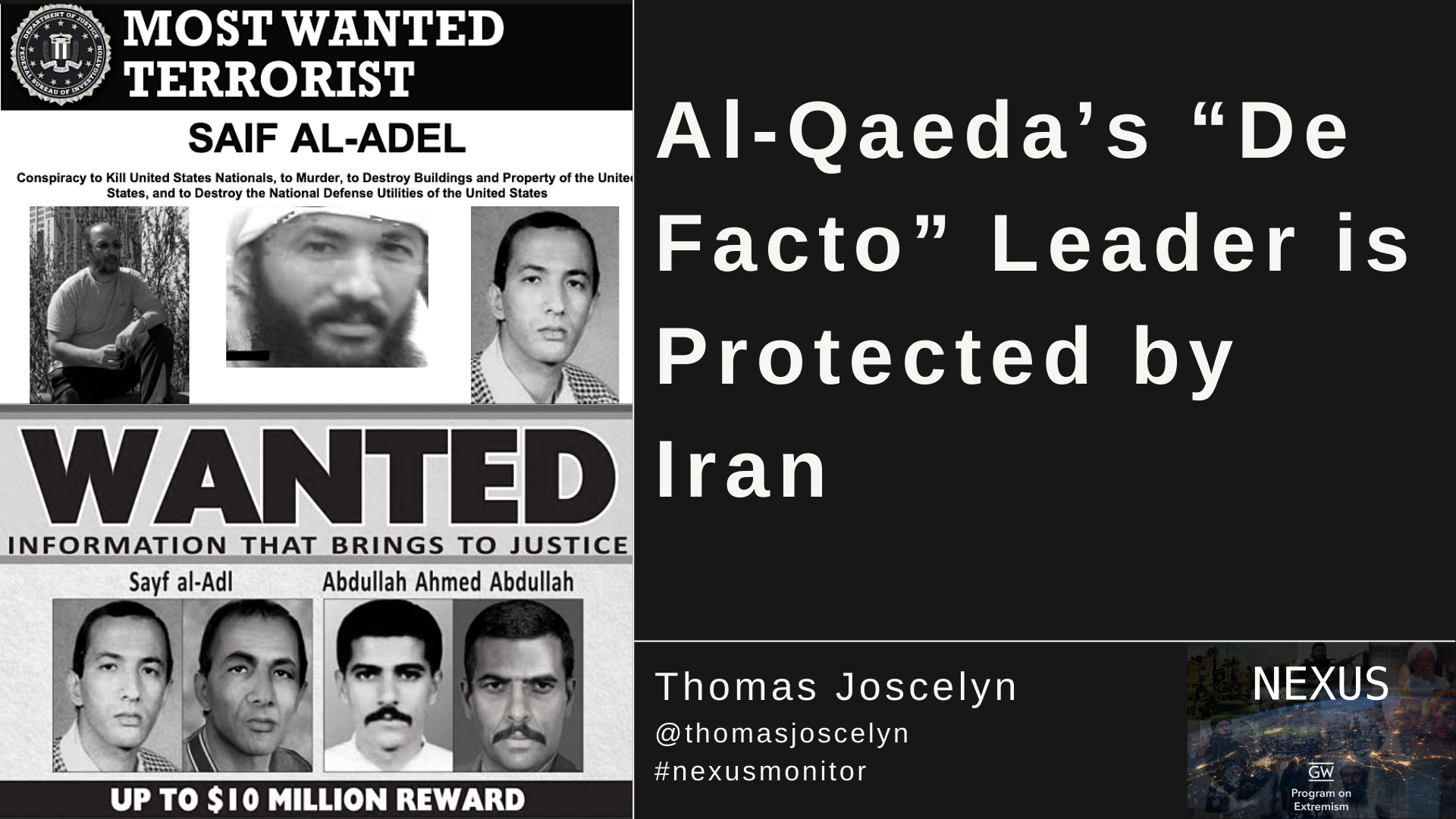

One month after al-Zawahri’s death, al-Qaeda still has not yet announced his successor; in fact, it has not even admitted that he is dead. Sources close to al-Qaeda leadership in Iran indicate that al-Zawahri is dead and that the group has initiated a leadership transition process, but have stopped short of issuing a public announcement. Whatever the movement’s true position on succession currently is, al-Qaeda remains resolved in its long-term anti-American political agenda. While al-Zawahri was alive, al-Qaeda sought to retain its political core in Afghanistan. Whether that remains the plan going forward will depend on who the next leader is.

Ever since the Taliban returned to power, at least one al-Qaeda affiliate, usually al-Qaeda in the Arabian Peninsula (AQAP)—which has traditionally coordinated more closely with the senior leadership—has unequivocally emphasized targeting the United States directly. But it is unclear how and when al-Qaeda seeks to strike, and how Afghanistan may or may not figure into planning for external attacks. These ambiguities could be the result of a near-term strategy of retaining Taliban support, which was also al-Qaeda’s main priority throughout the Taliban insurgency, and in particular during the years of U.S.-Taliban talks.

After the 2020 Doha agreement, in which the Taliban committed to not letting al-Qaeda use Afghan territory against other countries, the two appear to have had a dialogue regarding the parameters of their relationship and al-Qaeda’s future in Afghanistan. A summer 2020 letter penned by AQIS chief Osama Mehmood to the Pakistani Taliban provides compelling evidence. In the letter, Mehmood notes that Afghan Taliban leadership consulted al-Qaeda on the Doha agreement, and that al-Qaeda agreed to the language restricting its use of Afghan territory against the United States and its allies. Mehmood explains that the Doha agreement can be compared to the Treaty of Hudaybiyyah in Islamic history, in which the Prophet Muhammed agreed to a decade-long truce with the opposing Qurayshi tribe of Mecca. If Mehmood’s stance represents the broader al-Qaeda view on the Doha agreement, then al-Qaeda maybe willing to exercise restraint against the United States and its allies, at least from its positions in Afghanistan, but there is also likely an expiration date on the restraint.

At the same time, al-Qaeda seems weary of the criticisms it faces from Taliban constituencies that are more focused on local priorities, including the son of the former Taliban chief and current Minister of Defence, Mullah Yaqub. Al-Qaeda is also learning to carefully navigate the Taliban’s evolving engagement with the international community. Since seizing power, the movement has bid for membership at the United Nations, invited American investors back to the country (especially in the mining sector), and recently started engaging the Indian government, which has sought assurances of protection from both Pakistan-backed jihadis and al-Qaeda.

Al-Qaeda’s leadership likely understands that to offset those parts of the Taliban that are wary of associating with a global terrorist movement, they must retain the support of key power centers within the movement. In this context, al-Qaeda is likely to continue leaning on the support of the supreme leader and his inner circle of ulema, in addition to other major leaders such as Sirajuddin Haqqani. Al-Qaeda leadership may also work to counter potential Taliban over-commitment to the international community on counterterrorism issues, as well as likely block select major Taliban initiatives, such as gaining membership at the United Nations.

Challenges for U.S. Counterterrorism

The terrorism landscape in Afghanistan is dynamic, and it continues to fester due to the policies of the Taliban as the de facto state actor. While the worst-case scenario involving rapid al-Qaeda expansion and attacks against U.S. interests, allies, and the homeland is yet to materialize, it is still early days yet. The main thrust of U.S. policy in response appears to be containment of the threat through over-the-horizon strikes. Will that be sufficient?

Since the strike against al-Qaeda chief Ayman al-Zawahri, the Biden administration is arguing that it has proven its critics wrong by carrying out a precision strike in a denied area and eliminating a top terrorist target. They and other supporters of over-the-horizon strategy have contended that the successful strike on al-Zawahri is proof that the strategy works, and that the United States did not need to keep military forces in Afghanistan to manage remaining counterterrorism challenges. In part, these defensive arguments are motivated by the spate of criticism on the administration’s botched withdrawal from Afghanistan.

President Biden announces the death of Ayman al-Zawahri in a U.S. drone strike in Kabul on July 31, 2022.

The administration’s argument in support of over-the-horizon capabilities in Afghanistan is understandable; at one point last year, some U.S. intelligence officials derided the administration’s over-the-horizon plans as “over the rainbow”. Yet it would be a mistake to interpret the al-Zawahri strike as proof that over-the-horizon strikes face no major challenges, or that they are a silver bullet. It is important to put the strike in a comparative targeting perspective, especially in light of how the threat landscape is likely to evolve.

What the al-Zawahri strike demonstrates is that the United States is able to detect and neutralize dangerous threats in Afghanistan by generating viable intelligence on a target and accessing a denied area to eliminate it, most likely via aircraft flown from the Middle East into Afghanistan through Pakistani airspace. Al-Zawahri was a well-known, high-value target, and targets like him are hard to locate and eliminate, especially as they tend to have high levels of operational security. That said, he does not represent the hardest class of targets to find, fix, and finish. Because of his status as the top leader of al-Qaeda, the U.S. government had devoted extensive intelligence resources on his search. By the time of his death, al-Zawahri was familiar to America’s various targeting bureaucracies precisely because he had been hunted for so long. His signatures and habits were well-known, and he was leaving traces in recent months. In addition, the Taliban—in particular senior members of Sirajuddin Haqqani’s inner circle—had lowered their operational security precipitously in the months before al-Zawahri’s death. On the day of the strike, he was also at a sufficient distance from civilians.

In short, the U.S. government will confront harder targets than al-Zawahri in Afghanistan, ones who will likely work with the Taliban to prepare for and preempt potential American targeting. When the Taliban were only an insurgency, some al-Qaeda leaders close to the movement eluded U.S. targeting for a long time. Two targets that the U.S. government had an especially difficult time locating were al-Zawahri’s deputy, Shaikh Umar Khalil, and al-Qaeda’s longtime Afghanistan chief, Farooq al-Qahtani, who were less familiar to U.S. intelligence than al-Zawahri and received high levels of operational security from their protectors. As documented by journalist Wesley Morgan, the U.S. military’s Joint Special Operations Command (JSOC) failed to find al-Qahtani as part of its yearslong campaign, Operation Haymaker; only after his targeting was handed off to the CIA was al-Qahtani eventually located.

Another harder high-value target is the current leader of ISIS-K, Shahab al-Muhajir, who is responsible for the August 2021 attack at the Kabul airport during the U.S. evacuation that killed nearly 200 civilians and 13 U.S. service members. Like al-Zawahri, al-Muhajir receives the highest levels of operational security, partly because he is also in the crosshairs of the Taliban given the two’s extensive rivalry. And, like Khalil and al-Qahtani, Al-Muhajir is less familiar to those targeting him. If any externally-directed plotting activity takes place from within Afghanistan, the individuals responsible are likely to be less familiar to targeting officials than profiles like al-Zawahri and enjoy high levels of operational security.

Another question surrounding the al-Zawahri strike is whether it was spurred by insider information from the Taliban or information shared by a regional government like Pakistan. Many conspiracy theories regarding this question abound, especially within Afghanistan and the immediate region. Indeed, there is a complex history of covert Pakistani help through provision of intelligence, air space, and bases to facilitate U.S. drone strikes against al-Qaeda and some other targets in the Afghanistan-Pakistan region. There has also been speculation that the Taliban agreed to covert intelligence-sharing as part of the Doha accord. However, there is nothing definitive to support either Pakistan or the Taliban’s involvement in the al-Zawahri strike. Similar questions were raised following the 2016 targeting of then-Taliban chief Mullah Akhtar Mansoor near Quetta in Pakistan — that the Pakistani military had provided intelligence on Mansoor as he was drawing closer to Iran. Subsequent accounts, however, suggest that U.S. intelligence had been tracking his phone starting from a shopping trip in the UAE. Nevertheless, if it does materialize that insider Taliban or Pakistani information helped to develop the eventual strike on al-Zawahri, the implications would be profound. Beyond inflaming political tensions, the ability of the U.S. over-the-horizon counterterrorism posture to replicate a similar high-value targeting success would seem to depend not only on significant technical means, but also on hard-to-control political circumstances and partnerships that yield timely information.

Finally, how the Taliban may react to possible future American strikes remains an open question. The optimistic view reflected in the assessments provided to President Biden before the al-Zawahri strike is that the Taliban are sufficiently constrained to not retaliate in a meaningful way. Some in the U.S. military have speculated that the strike may compel the Taliban to reconsider their options altogether, and perhaps work with the U.S. against mutual threats like ISIS-K. These perspectives appear overly optimistic. The reality is that the Taliban’s threshold for cooperation remains opaque to outsiders, but they continue to search for coercive leverage over their neighbors, and have even threatened Pakistan in the event of more strikes. There are also second-order effects to consider when it comes to Western humanitarian NGOs in Afghanistan. After the al-Zawahri strike, these organizations paused their movement to gauge the Taliban’s response. If, in the future, the Taliban decide to retaliate against Western aid workers in response to U.S. airstrikes, they could cause irreparable damage to the global humanitarian effort to support the Afghan population. Future airstrikes must carefully contend with the prospects of Taliban retaliation and the political options necessary to ward off the prospect of unintended escalation.

Endnotes

[1] Information relayed to the author during interviews with informed interlocutors on the ground.

[2] Information relayed to the author during interviews with informed interlocutors on the ground.