ON AUGUST 10, the Islamic State’s Central Africa Province (ISCAP), also referred to as ISIS-DRC and known locally as the Allied Democratic Forces (ADF), freed almost 800 inmates in a prison break in the eastern Congolese city of Butembo. This raid, which marked the group’s first major foray inside Butembo, was another reminder of ISIS-DRC’s arguably expanding capabilities inside eastern Congo despite extensive military operations against it.

At the same time, ISIS-DRC’s operations following the start of joint Ugandan-Congolese military operations against it last November, showcase just how its Islamic State identity influences its strategic approach. This strategic calculus, which includes taking on more audacious operations like the Butembo jailbreak, can only be further understood when contextualized within ISIS-DRC’s operations as a whole. ISIS-DRC has been able to exploit shifting local and regional dynamics in eastern Congo, allowing for the expansion of the Islamic State’s violence and ideology across central Africa.

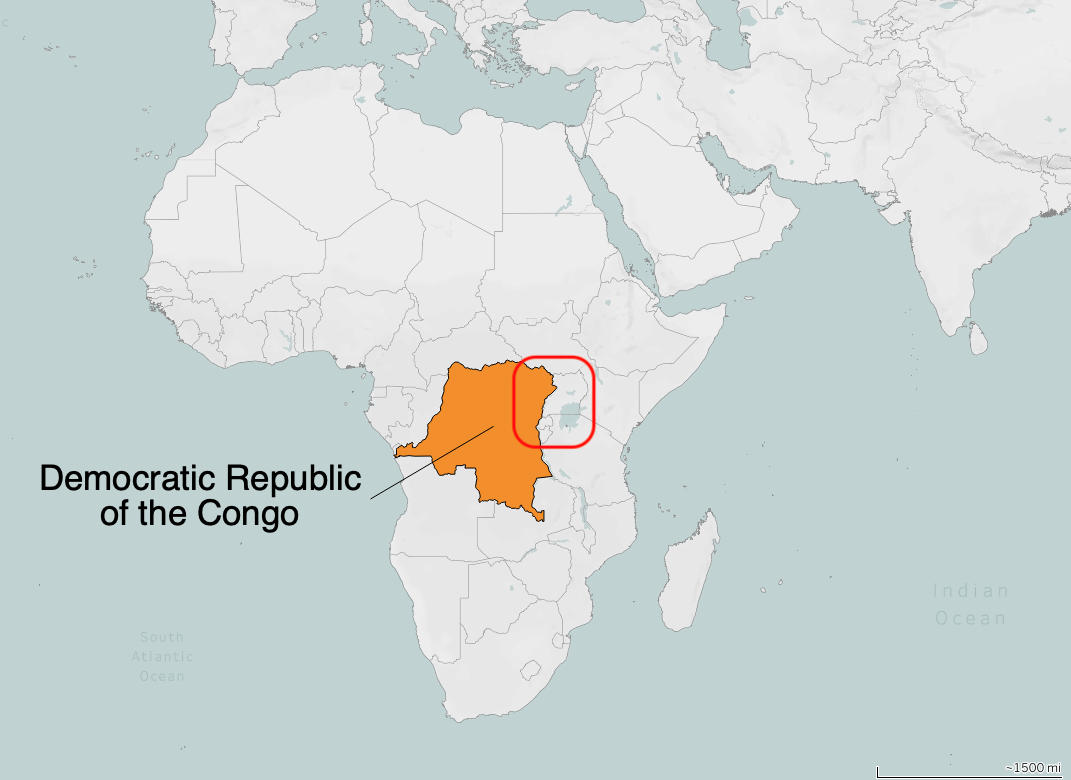

Location of the Butembo prison break.

The Butembo Attack

Early in the morning on August 10, approximately 80 Islamic State fighters launched a coordinated assault on the central Kakwangura prison inside Butembo. The operation, which reportedly only lasted around 15 minutes, left at least five ISIS-DRC members, two police officers, and one civilian dead. Almost 800 inmates were freed, with Congolese officials contending that at least 250 inmates have since been recaptured. The jihadists then withdrew with the freed inmates back to ISIS-DRC’s bases in eastern Congo’s Mwalika Valley, an area within Virunga National Park 30km northeast of Butembo, clashing with Congolese security and civilian militias along the way.

The Islamic State released three claims for the attack, one the following day and two more detailed accounts on August 12. Both the August 12 claims are notable for their use of the phrase “break the walls,” explicitly linking the incident to the Islamic State’s long-standing “Breaking the Walls'' campaign that encourages its affiliates to attack prisons. This is the group’s third such attack in Congo in the last two years, first freeing at least 1200 inmates from Beni’s Kangbayi prison in October 2020 before attacking the much smaller Nobili prison in February 2022. The latter, although only freeing around 20 prisoners, was strategically notable as it occurred at the major border crossing for Ugandan troops entering Congo for the joint Operation Shuja and only 15km from the town of Mukakati, the operation’s headquarters.

The August 10 assault marked the group’s first major attack inside Butembo. The city has recently witnessed a surge of unrest, particularly in regards to anti-United Nations protests that occurred throughout eastern Congo. Demonstrations against the UN in Butembo left at least seven protestors and three UN personnel dead last month. This follows at least 21 attacks on civilians and security forces since the beginning of the year by unidentified armed actors or local Mai-Mai militants (or community-based militias), according to data from the Kivu Security Tracker, a local conflict monitoring project.[1]

This persistent instability in the city and in surrounding areas, in particular the violent protests in late July, may help explain ISIS-DRC’s ability to enter deep into the city unopposed and quickly return to its staging points to the northeast, effectively exploiting the chaos. The Islamic State’s Congolese affiliate has previously launched attacks into the Bashu Chiefdom, a highland area overlooking the Mwalika area to the east of Butembo, but no confirmed Islamic State attack has reached closer than 8km from Butembo’s eastern districts.[2] That such a large group of fighters was able to climb Bashu’s steep hills and traverse its heavily populated rural areas before staging an incursion deep into Butembo’s urban areas belies both ISIS-DRC’s capacity for coordinated operations and the permissive security environment enabled by overstretched security forces attempting to deal with a multitude of threats.

Contextualizing the Butembo Prison Break

While significant in its own right, the prison break in Butembo is also illustrative of the Islamic State’s continued expansion in the face of sustained military pressure from Operation Shuja. Following last November’s triple suicide bombing in Kampala, Uganda, the Ugandan military launched joint operations on November 30 against ISIS-DRC alongside the Congolese military. Although the group has abandoned some of its bases in the face of these operations, its ability to commit violence has remained unchanged[3] as it has moved into new territories and returned to areas it had long since abandoned.

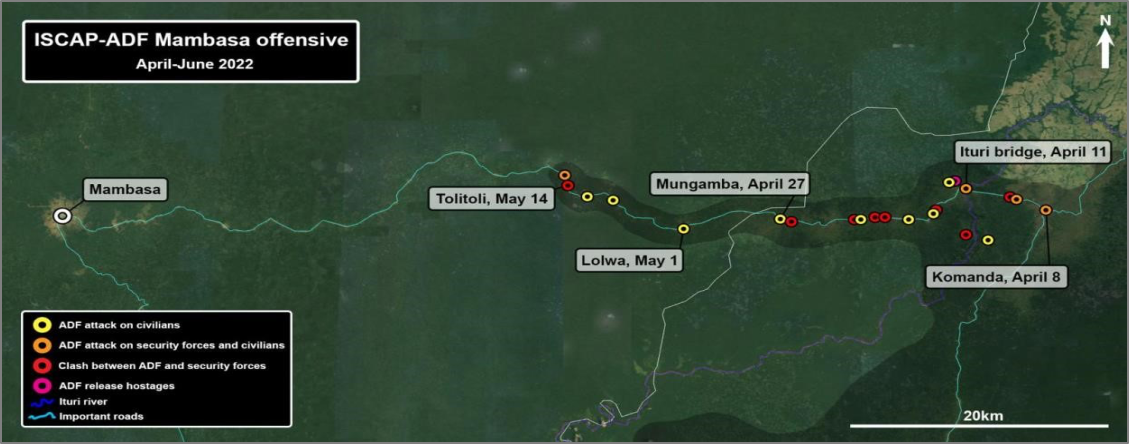

For example, Operation Shuja’s seizure of ISIS-DRC’s headquarters at Kambi ya Yua in Beni territory in December 2021 drove much of the group’s top leadership north into Irumu Territory of Ituri province, where other elements of the jihadist group have been operating since at least early 2021. From there, ISIS-DRC has pushed west towards Ituri’s Mambasa Territory, crossing the Ituri River for the first time and reaching within 40km of Mambasa town itself (see Figure 3). This push deeper into Mambasa was ominously preceded on April 11 by a massacre on and near the bridge over Ituri River itself, in which the group killed 24 people.

Beginning in early April, ISIS-DRC has pushed steadily west into Mombasa territory, entering areas far outside its normal area of operations.

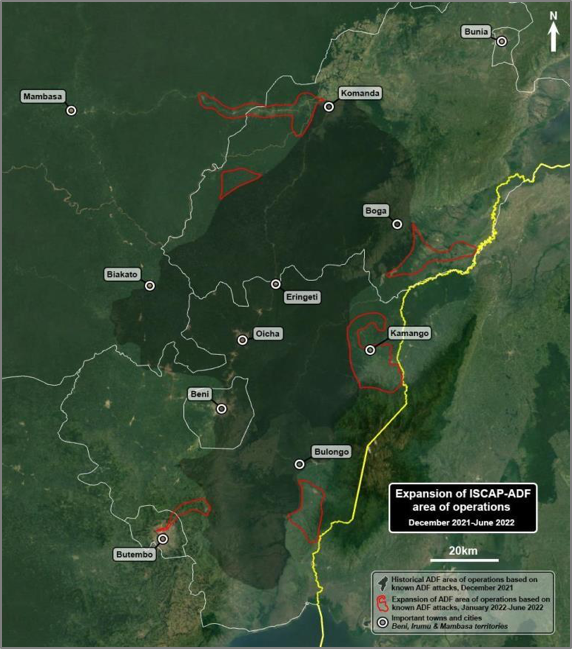

Similarly, the last six months have also witnessed a territorial push on the southern limit of the group’s traditional area of operations in Beni territory’s Bashu region, though this expansion of attacks has covered less distance than ISIS-DRC’s offensive into Mambasa. In November, the jihadist group mounted at least three attacks into Bashu, including an assault that killed 38 civilians in Kisunga, approximately 10km east of Butembo. In February of this year the group struck the farthest south it ever had, attacking the town of Karuruma and a nearby village three times between February and March. Four months later, on July 20, the Islamic State’s Congolese wing assassinated Abdalatif Patanguli Kalemire, a 90-year-old customary chief and the patriarch of a prominent political family, and his wife in Bulambo, a town approximately 10km northeast of Butembo. The Islamic State’s central media apparatus was quick to claim the attack, describing Patanguli as a former Armed Forces of the Democratic Republic of the Congo (FARDC) officer and making it clear they had targeted him.

Beyond pushing into new areas, ISIS-DRC also began returning to its historic area of operations in Watalinga and southeast Rwenzori this year (see Figure 4). Thus, the jihadist group has reestablished control over areas that it largely abandoned over a decade ago. These moves appear to be in response to ongoing military operations against it, as the group’s violence forced mass displacements towards Shuja’s main border crossing between Uganda and Congo, undermined the communities’ confidence in the militaries’ ability to protect them, and created new ISIS-DRC strongholds deep in the jungle.

Since the beginning of the current military operations, ISIS-DRC has returned to some

of its historic areas of operations while also pushing into new territories.

In addition to the group’s expansion around its traditional area of operations, ISIS-DRC also perpetrated its first known attack in Goma, the provincial capital of North Kivu, which lies hundreds of kilometers south of its camps in Beni Territory. In April, the group conducted a suicide bombing on a military camp inside Goma, killing at least six people. While Congolese officials initially downplayed the attack and blamed it on an errant hand-grenade, later investigations have found the explosion was indeed the result of an improvised explosive device (IED) worn by a female suicide bomber.

With the Goma bombing, ISIS-DRC has now conducted five suicide operations using seven bombers since first implementing the tactic in June 2021. This list includes a suicide bombing in Beni, DRC, in June 2021, a failed suicide bombing outside of Kampala, Uganda, in October, the three simultaneous suicide bombings in Kampala in November, and another suicide bombing in Beni in December. An attempted suicide bombing plot in northern Uganda was also thwarted last August.

Despite these developments, the fight against the Islamic State’s Congolese wing has faced mounting external pressure as other conflicts have divided the Congolese military’s attention. In particular, in May, FARDC began redeploying troops south to Rutshuru territory[4] to confront the renewed M23 rebellion, which in 2012 succeeded in briefly capturing Goma before eventually being defeated by a joint UN-FARDC force. In addition to the territorial threat M23 poses, this conflict has flamed regional tensions as Congo has repeatedly accused Rwanda of supporting M23, an accusation the United Nations recently affirmed. ISIS-DRC, already expanding despite a concentrated offensive, now appears to be taking advantage of the security vacuums created by FARDC redeployments to stage increasingly daring attacks.

Islamic State Celebrates its Affiliate in the Congo

ISIS-DRC’s operations, especially in Mambasa and now the Butembo prison break, have been heavily promoted by the Islamic State’s central media apparatus this year. In its ideological need to highlight continual expansion of its caliphate, the Islamic State has enthusiastically put its Congolese affiliate’s operations in the context of its globalized insurgency. At the same time, ISIS-DRC continues to show its enthusiasm as a regional Islamic State affiliate by abiding by the Islamic State’s media and operational diktats.

For example, the raid in Butembo generated three separate attack claims, as well as a photo released from inside the prison, a brief video of the prison break itself, and another video showing the freed prisoners joining the group in the areas the Islamic State claims it controls. In the first video, two ISIS-DRC members can be seen opening the cell doors, yelling “Islamic State - Baqiya [remaining],” while hundreds of inmates flee the prison. In the second video, freed Christian prisoners are shown converting to Islam while others allegedly join ISIS-DRC after a greeting ceremony.

As previously mentioned, the prison break in Butembo is the second major operation carried out by ISIS-DRC since 2020. In October of that year, the group also released at least 1,200 inmates in an assault on the Kangbayi prison in Beni town. The Congolese group was quick to claim the operation in the name of the Islamic State on its social media channels, adding that the operation was done in response to a recent call for jailbreaks by the Islamic State’s then-spokesman Abu Hamza al-Quraishi. Much like its propaganda with Butembo, the Islamic State itself also heavily promoted the Kangbayi jailbreak as part of its global “Breaking the Walls” campaign.

The Islamic State’s “breaking the walls” campaigns often act as a boon for jihadists, boosting morale, troop numbers, and even capabilities if experienced or well-trained individuals are freed. In more recent years, other jailbreaks within this campaign have been conducted in Syria, Afghanistan, the Sahel, Nigeria, Southeast Asia, and Central Asia. While the Butembo prison break has been among the most prominent attacks featured within the Islamic State’s propaganda from Congo, it has not been the only ISIS-DRC operation promoted by the global jihadist group in recent months. Indeed, ISIS-DRC’s Mambasa operations have also played a sizable role in its media production from the DRC. Since April, the Islamic State has released 14 attack claims (representing 16% of all DRC claims released since April), 33 photos (23% of all photos since April), and two videos (33% of all videos since April) from the area.[5]

This fits with a wider trend of the Islamic State’s promotion of its Congolese affiliate’s activities in the wake of the Ugandan intervention. Since the beginning of the year, the Islamic State has claimed 122 attacks inside Congo, or roughly over a third of its total claimed operations inside the country since 2019.[6] Additionally, the Islamic State has also released 191 photos and seven videos from Congo since the beginning of the year.[7] By doing so, the Islamic State has been able to maintain its ideological need for expansion, in that its global franchises continue to grow and operate in continuously newer areas by promoting its activities in the Congo.

In providing these claims and media productions to the Islamic State’s central media apparatus, it is also clear the Congolese franchise continues to abide by the Islamic State’s rules and guidelines for its regional affiliates. For instance, in the aforementioned second video after the Butembo prison break, an ISIS-DRC fighter gives a short speech in Arabic in which he declares:

“This message is for the Congolese Christian rulers: For our war with you is a religious one, not an ideological one nor a tribal one. We are content to fight you until the laws of God above rules over this land and will continue until God establishes one of these three for you: Islam, Jizya [tax paid by non-Muslims], or [continuous] Fighting.”[8]

These lines are eerily similar to an Islamic State Mozambique video released earlier in August. It is clear from the similarities that the Congolese affiliate likely abided by media guidelines ostensibly provided by the Islamic State to have common language in the videos. Other examples of ISIS-DRC likely abiding by these rules in its media includes the use of black kanzus [or thobes] to harken back to the Islamic State’s reign of terror in Iraq and Syria, extreme hyper-violence such as graphic beheadings, and participation in global media campaigns such as the Islamic State’s yearly Eid photo celebrations.

An ISIS-DRC fighter provides a speech following the Butembo prison break, which was released by the Islamic State’s official Amaq News Agency channel.

Conclusion

The Butembo raid – a massive prison break inside a significant city that ISIS-DRC had previously never attacked – was a milestone for the Islamic State’s affiliate in DRC. However, in many ways, the attack was the next logical steps in the face of the group’s growing capabilities, territory, and ambition. These developments, while already worrying, are rendered more alarming by the recognition that they have succeeded in the face of sustained joint military operations against the jihadist group.

With ISIS-DRC’s continued expansion in the face of Operation Shuja, it is clear that an integrated approach is necessary. The group has predictably reached unprecedented levels of lethality and proven itself distressingly adaptable since joining the global Islamic State network in 2017. Nevertheless, it still operates in, and to a certain extent is shaped by, the complicated local dynamics that have hindered past attempts to defeat it, much like how other regional Islamic State affiliates are shaped by their own local dynamics. Eastern Congo’s myriad ongoing conflicts, such as the current M23 crisis, divert desperately needed resources from the fight against the jihadist group, while local grievances against the UN and government actors create space in which the group can operate more freely. Recognizing the place of military intervention while also working to address local community needs and cutting off support from the Islamic State’s regional networks is essential to halting and ultimately reversing the Islamic State’s Congolese expansion.

Endnotes

[1] Based on authors’ analysis of data compiled by the KST.

[2] Ibid.

[3] According to the authors’ analysis of data from the Kivu Security Tracker (KST), the monthly average of civilians killed by ISIS-DRC throughout 2021 stood at around 105 civilians. In the first six months of 2022, during which time the group has continuously faced joint military operations, KST data show ISIS-DRC’s average monthly death toll is up to 116 civilians.

[4] Tweet by Filip Reyntjens (@freyntje) on August 11, 2022, contains a link to the original source. Information cited is in paragraph 85 of linked report.

[5] Based on authors’ datasets of Islamic State Central Africa Province operational claims and of its media productions.

[6] Based on authors’ dataset of Islamic State Central Africa Province operational claims.

[7] Based on authors’ dataset of Islamic State Central Africa Province media productions.

[8] Amaq News video, released on Aug. 17, 2022.